家用機器人:

交織性研究方法

議題

家用機器人有潛力透過執行家務以及提供個人助理和照護來提高生活品質。為取得成功,家用機器人需要能夠在具有不同環境以及使用者類型、價值觀和權力關係的家庭中工作。

方法:分析社交機器人的社會性別與交織性

家用機器人的用途管理有許多複雜性。這些機器人需要以不同的方式設計,以適應多樣的生活空間、建築風格、家庭使用者以及空間中的非人類,例如寵物或植物。機器人可以影響家庭和更廣泛的勞動生態系統中的社會動態。重要的是考慮機器人如何建立信任、滿足使用者的功能需求,以及可以訂製去配合家庭成員的價值觀。為了實現這些目標,機器人設計師可以在設計過程中的每個步驟當中,採用不同形式的交織性方法,並讓潛在的家庭終端使用者加入共創和參與設計。

性別化創新:

- 1. 了解不同家庭的需求和偏好,可以讓機器人適用於不同的環境以及家中的多重使用者。

- 2. 機器人與家庭之間的價值協同(value alignment)是設計過程的關鍵部分,涉及理解個別家庭的價值觀和規範—包括文化和社會性別差異如何影響家務。

- 3. 克服訓練和部署之間的域差距(domain gap):訓練場景和部署環境在空間和人際關係方面經常有不協調的情形。透過訓練任務、設定以及評估指標的多樣性來縮小域差距,是成功地使用家用機器人的關鍵。

- 4. 處理家庭內以及全球的權力動態:機器人專家必須考慮機器人如何影響家庭和更廣泛的勞動市場的社會動態。

議題

性別化創新1:了解不同家庭的需求和偏好

性別化創新2:機器人與家庭之間的價值協同

性別化創新3:克服培訓和部署間的域差距(domain gap)

性別化創新4:處理家庭內和全球的權力動態

結論和下一步

議題

家用機器人有潛力透過執行家務以及提供個人助理和照護來提升人類的生活品質。使用者可能包括需要額外支援才能留在家中的年長者、需要教育支援的兒童、有特定情況或障礙而需要輔助照護的人、需要幫忙一般家務(例如清潔、烹飪、折衣服)的人。通常在這些任務落在了婦女的肩上,這與她們的階級和經濟地位有關。重要的是,應考慮設計機器人時,要跨越不同環境的交織性面向。

同樣重要的是考慮機器人如何建立信任、滿足使用者的功能需求,以及可以訂製去配合家庭成員的價值觀。這些價值觀可能因文化和家庭類型(例如,單身、有家庭、有同居者)以及家庭中的個人而異;它們很靈活,並可能隨著時間而變化。為了實現這些目標,機器人設計師可以在設計過程中的每個步驟採用不同形式的交織性分析,並與潛在的家庭終端使用者合作設計機器人。

性別化創新1:了解不同家庭的需求和偏好

家用機器人需要支持生活在不同類型家庭中的各種人們(圖1)的可及性、尊嚴、偏好和自我效能。這些可能包括:

- 獨居者、家庭、室友(同居者/同住人)、中途之家、公共家園

- 障礙人士

- 不同年齡、身高和體重的人

- 不同社會性別、族群和種族、語言和文化的人

- 房客和訪客

- 非人類,尤其是寵物和植物。

機器人需要適合不同的建築形態,例如:

- 獨棟房屋

- 連棟房屋

- 公寓

機器人也需要針對不同配置的生活空間進行設計,例如:

- 智慧家居

- 基礎設施(電力、插座、網路)

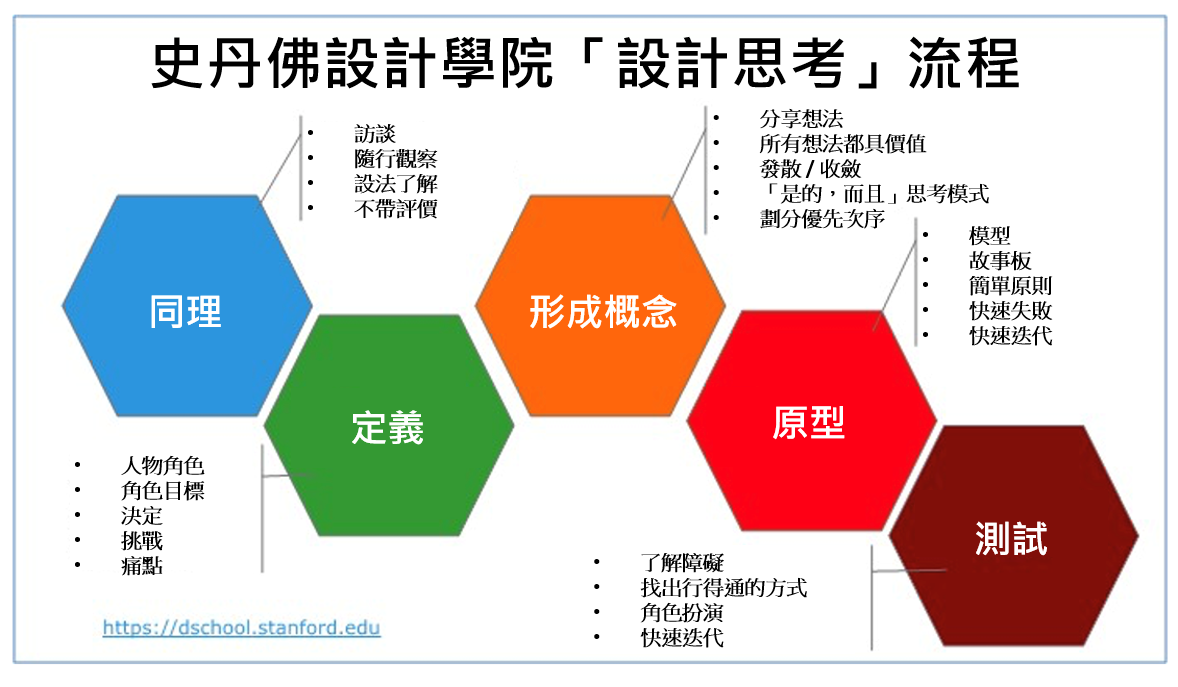

迭代設計(iterative design)過程能夠使設計人員檢查其假設,並更加了解機器人使用的結果(關於社會性別,請參閱社會性別影響評估)。在設計過程中納入使用者可以提升解決方案反映出他們的不同需求和偏好的可能性。

圖1. 設計思考流程連同交織性分析可用於開發更具包容性的家用機器人設計。Stanford d.School, 經授權使用。

性別化創新2:機器人與家庭之間的價值協同(value alignment)

機器人的活動、行為、溝通和資料處理應符合:

- 每位家庭成員的價值觀(例如,他們的家庭空間、隱私程度、自主性、平等、整潔和自我效能)

- 家庭常規(例如,責任和權力關係)。

深入了解文化和社會性別差異如何影響家務勞動以及潛在的(內隱和明確的)價值觀和常規,有助於設計適合情境的機器人。

方法:共創和參與式研究設計

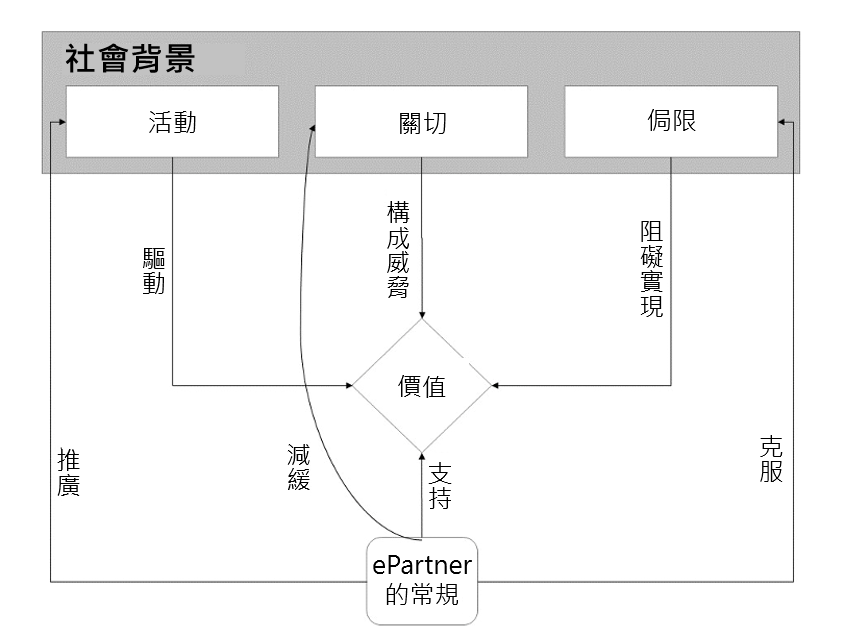

一個關鍵步驟是將價值常規模型建構入機器人的知識庫,使其能夠充當家務中的伙伴(見圖2)。

圖2:價值常規模型(Kayal et al.,2019)。這個價值常規模型需要針對特定的機器人家務(例如,保持距離並處理其覺察到的污垢資訊)舉例說明。機器人應該能夠向不同的家庭成員解釋常規以及其本身與常規相關的行為(例如,常規的起源和原因)(Miller,2019)。請留意,常規應支持包容性(例如,障礙家庭成員的特定支持需求,這可能需要更強的機器人自主性)。

有關價值敏感設計(value-sensitive design)的更多資訊,請參閱Friedman et al.(2017);有關價值提取方法(value elicitation methods)和價值故事工作坊,請參閱 Harbers et al.(2015);而有關紮根理論,請參閱Kayal et al.(2019)以及Cremers et al.(2014)。

使用者需要了解,對於特定價值的選擇如何影響機器人的表現。例如,如果家庭選擇將資料保存於本機以保護隱私,機器人可能會學得較慢(圖3)。

圖3:針對涉及價值觀張力的機器人活動,家用機器人及其使用者需要建立常規並達成協議。Photo Credit: Pikbest。

性別化創新3:克服培訓和部署間的域差距(domain gap)

機器人需要在多樣的家庭環境中與各種人們一同工作。設計和部署之間的差距可能源於:

- 培訓場景與部署環境之間的不協調。

- 這種不協調可能存在於機器人的視覺感知中(Wang et al.,2019)。必須訓練機器人的視覺感知以認識多樣性,例如,用於交接任務的慣用手(右撇子、左撇子或雙手通用)(Kennedy et al.,2017)。

- 這種不協調可能存在於機器人語言感知中。例如,設計人員可預見機器人遇到特定群體(例如兒童)時的語音識別能力會降低,於是在對話中建構多模態修復機制,以便機器人能夠理解並繼續對話(Ligthart et al,2020)。

- 開發者和居家使用者對機器人的期望和看法不協調(Lee et al.,2014)。例如,使用者和機器人專家對機器人的看法可能不同,尤其是類人機器人和社交機器人(Thellman et al., 2022;性別化社交機器人)。偏見可能出現在使用者(Tay et al.,2014;Perugia et al.,2022)或機器人專家(Robertson,2010;Seaborn & Frank,2022)。

這些不協調可能根植於機器人專家在建構系統時可用的背景資訊(圖4)。這可能包括問題定義、功能選擇以及用於訓練場景和部署環境的機器學習資料來源。

圖4. 真實房屋(左)與機器人模擬器中房屋(右)的域差距。Photo credit: Selma Šabanović;Ruohan Zhang,由Stanford Vision and Learning Lab開發之BEHAVIOR-1K,經授權使用。縮小訓練和部署之間的域差距,需要在訓練任務、環境和評估指標方面確保多樣性。開發人員可以在示範、說明和互動中考慮這種多樣性。他們可以透過讓潛在的終端使用者參與設計過程,進一步確保機器人滿足使用者需求(Olivier et al.,2022;Barnes et al.,2017;Lee et al.,2017)。

多任務學習和對抗式訓練等新的機器學習方法,也可用於減低模型偏差(Benton et al.,2017;Zhang et al.,2018)。這些方法可促使機器人依據不同環境中的多樣使用者提升其表現,雖然目前機器人技術尚未廣泛如此做。此外,批判地考慮資料來源、特徵擷取(feature extraction)的各種方法,和由此產生的機器學習模型也很重要,如此可以辨別和處理潛在的偏見來源。應在機器人設計和應用中明確說明其限制。

性別化創新4:處理家庭內和全球的權力動態

將機器人引入居家,可能有意或無意地影響人們之間的社會動態。

家內的權力動態。機器人可能會介入家庭互動。當一個機器人將麥克風轉向一個話不多的人,可能會激發更平等的輪流對話(Tennent et al.,2019)。機器人透過奉承或畏縮來回應家庭內消極或憤怒的互動,可能會促使家庭成員反思他們的互動並可能加以改善(Rifinski et al.,2021)。因此,考慮機器人如何直接或間接影響家庭的權力動態是很重要的。納入終端使用者,並在真實的家庭環境中訂製機器人的性能,可以在此類互動過程中,讓設計者設計的機器人和使用者控制之間的互動達到平衡。

身體虐待。機器人應該被設計來介入家庭暴力嗎?初步研究顯示,兒童比成人更有可能向機器人訴說虐待行為(Bethel et al.,2016)。機器人應該如何應對危險情況?機器人的設計是否應該包含通報功能?他們又將向誰通報?使用者是否需要選擇加入/退出這些功能?(尤其是)在家庭成員意見不合的情況下,是哪個成員下決定?處理這些懸而未決的問題,產品需要具備使用者敏銳度。

克服刻板印象。部署在家中的機器人需要有潛力挑戰家務勞動的社會性別分工。例如,Roomba機器人激發青少年和男人更常吸塵(Forlizzi,2007)。機器人還可以提醒家庭成員做家務,從而消除女性的這類情緒勞動(Dobrosovestnova,2021)。

更廣泛的權力動態。只要機器人不是完全自主的,它們就可能部分由遠程工作人員控制—在不久的將來,零工經濟可能會從MTurk(譯註:亞馬遜土耳其機器人。Amazon開發的群眾外包平台,下單者可要求工作人員完成特定任務。)轉向機器人技術(例如,Mandlekar et al.,2018)。在某些情況下,這可以產生積極的成果,東京的DAWN Avatar Robot Café(譯註:設有特定的座位區,由機器人專門服務。)就是一個範例。DAWN機器人主要由障礙人士遠端控制,從而使多樣的人們參與更廣泛的社交網絡。然而,平等不是給定的。在全球服務經濟中,已開發國家使用的照護機器人正由來自低收和中等收入國家的人們遠端操作,引發了有關勞動條件、全球勞動力擷取和流動的關鍵問題(Guevarra,2018)。機器人可能需要挑戰已部署環境中的既有規範。批判常規的創新(norm-critical innovation)可以質疑那些讓各種形式的歧視長久存在的權力關係。

結論

家用機器人有潛力,它可以透過承擔家務和家庭維護以及提供個人助理和照護來大大改善人類的生活品質。藉由讓機器人專家和使用者共同設計這些機器人,以機器人設計的交織性面向作為核心是非常重要的。為了公平以及和性能的品質,開發人員必須考慮如何使機器人可制訂成在一個家庭中,建立起信任,滿足不同使用者的功能需求,並適合家庭價值的範圍。同樣重要的是考慮如何提升家庭內的做事方法,而不是簡單地將機器人當作OK蹦去治療一個需要改進程序的體系。例如,未來的家用機器人可能會具備針對家庭成員的社會角色及其互動(包括負面的)的敏銳度,並以道德的、以價值為中心的方式回應。

Works Cited

Barnes, J., FakhrHosseini, M., Jeon, M., Park, C.-H., & Howard, A. (2017). The influence of robot design on acceptance of social robots. 2017 14th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1109/URAI.2017.7992883

Benton, A., Mitchell, M., & Hovy, D. (2017). Multi-task learning for mental health using social media text (arXiv:1712.03538). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1712.03538

Bethel, C. L., Henkel, Z., Stives, K., May, D. C., Eakin, D. K., Pilkinton, M., Jones, A., & Stubbs-Richardson, M. (2016). Using robots to interview children about bullying: Lessons learned from an exploratory study. 2016 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 712–717. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2016.7745197

Cremers, A. H. M., Jansen, Y. J. F. M., Neerincx, M. A., Schouten, D., & Kayal, A. (2014). Inclusive design and anthropological methods to create technological support for societal inclusion. In C. Stephanidis & M. Antona (Eds.), Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Design and Development Methods for Universal Access (pp. 31–42). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07437-5_4

Dobrosovestnova, A., Hannibal, G., & Reinboth, T. (2022). Service robots for affective labor: A sociology of labor perspective. AI & SOCIETY, 37(2), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01208-x

Forlizzi, J. (2007). How robotic products become social products: An ethnographic study of cleaning in the home. 2007 2nd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1145/1228716.1228734

Friedman, B., Hendry, D. G., & Borning, A. (2017). A Survey of value sensitive design methods. Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction, 11(2), 63–125. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000015

Guevarra, A. R. (2018). Mediations of care: Brokering labour in the age of robotics. Pacific Affairs, 91(4), 739–758. https://doi.org/10.5509/2018914739

Harbers, M., Detweiler, C., & Neerincx, M. A. (2015). Embedding stakeholder values in the requirements engineering process. In S. A. Fricker & K. Schneider (Eds.), Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality (pp. 318–332). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16101-3_23

Kayal, A., Brinkman, W.-P., Neerincx, M. A., & van Riemsdijk, M. B. (2019). A user-centred social commitment model for location sharing applications in the family life domain. International Journal of Agent-Oriented Software Engineering, 7(1), 1–36.

Kennedy, J., Lemaignan, S., Montassier, C., Lavalade, P., Irfan, B., Papadopoulos, F., Senft, E., & Belpaeme, T. (2017). Child speech recognition in human-robot interaction: Evaluations and recommendations. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/2909824.3020229

Lee, H. R., Šabanovic, S., & Stolterman, E. (2014). Stay on the boundary: Artifact analysis exploring researcher and user framing of robot design. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1471–1474. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557395

Lee, H. R., Šabanović, S., Chang, W.-L., Nagata, S., Piatt, J., Bennett, C., & Hakken, D. (2017). Steps Toward Participatory Design of Social Robots: Mutual Learning with Older Adults with Depression. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1145/2909824.3020237

Ligthart, M. E. U., Neerincx, M. A., & Hindriks, K. V. (2020). Design patterns for an interactive storytelling robot to support children’s engagement and agency. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319502.3374826

Mandlekar, A., Zhu, Y., Garg, A., Booher, J., Spero, M., Tung, A., Gao, J., Emmons, J., Gupta, A., Orbay, E., Savarese, S., & Fei-Fei, L. (2018). ROBOTURK: A crowdsourcing platform for robotic skill learning through imitation. Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Robot Learning, 879–893. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v87/mandlekar18a.html

Miller, T. (2019). Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence, 267, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2018.07.007

Mioch, T., Peeters, M. M. M., & Neerincx, M. A. (2018). Improving adaptive human-robot cooperation through work agreements. 2018 27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 1105–1110. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROMAN.2018.8525776

Olivier, M., Rey, S., Voilmy, D., Ganascia, J.-G., & Lan Hing Ting, K. (2022). Combining cultural probes and interviews with caregivers to co-design a social mobile robotic solution. IRBM. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irbm.2022.06.004

Perugia, G., Guidi, S., Bicchi, M., & Parlangeli, O. (2022). The shape of our bias: Perceived age and gender in the humanoid robots of the ABOT database. Proceedings of the 2022 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 110–119. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3523760.3523779

Rifinski, D., Erel, H., Feiner, A., Hoffman, G., & Zuckerman, O. (2021). Human-human-robot interaction: Robotic object’s responsive gestures improve interpersonal evaluation in human interaction. Human–Computer Interaction, 36(4), 333–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2020.1719839

Robertson, J. (2010). Gendering humanoid robots: Robo-sexism in Japan. Body & Society, 16(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X10364767

Seaborn, K., & Frank, A. (2022). What pronouns for Pepper? A critical review of gender/ing in research. Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3501996

Singh, M. P. (1999). An ontology for commitments in multiagent systems. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 7(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008319631231

Tay, B., Jung, Y., & Park, T. (2014). When stereotypes meet robots: The double-edge sword of robot gender and personality in human–robot interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.014

Tennent, H., Shen, S., & Jung, M. (2019). Micbot: A peripheral robotic object to shape conversational dynamics and team performance. 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1109/HRI.2019.8673013

Thellman, S., de Graaf, M., & Ziemke, T. (2022). Mental state attribution to robots: A systematic review of conceptions, methods, and findings. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction (THRI), 11(4), 1-51. https://doi.org/10.1145/3526112

Wang, T., Zhao, J., Yatskar, M., Chang, K.-W., & Ordonez, V. (2019). Balanced datasets are not enough: Estimating and mitigating gender bias in deep image representations. 5310–5319. https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_ICCV_2019/html/Wang_Balanced_Datasets_Are_Not

_Enough_Estimating_and_Mitigating

_Gender_Bias_ICCV_2019_paper.htmlZhang, B. H., Lemoine, B., & Mitchell, M. (2018). Mitigating unwanted biases with adversarial learning. Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1145/3278721.3278779