人類乳突病毒(HPV)的奈米檢驗科技:重新思考研究優先次序與結果

摘要

本性別化創新方案係應歐盟委員會要求對其框架計劃7(Framework Programme, FP7)中的幾個項目進行分析。本案例研究對「增強基於奈米多重性技術生物測定平台於診斷應用的靈敏度」(NANO-MUBIOP)方案進行探討。我們對性別化創新以及分析生理性別和社會性別的方法予以確定,並指出了潛在的「增值」可能性。

議題

人類乳突病毒(Human Papillomavirus , HPV)的感染「估計造成[...]100%的子宮頸癌病例」,並促進了男/女性其他癌症的發病率,包括肛門癌、口腔和口咽癌、以及生殖器方面的癌症等(WHO, 2008b)。全球每年約275,000人死於子宮頸癌-其中80%發生在醫療資源有限的國家(Sankaranarayanan et al, 2012)。現有的HPV檢測提供了良好的靈敏度和特異性,但是在發展中國家,卻因為成本因所而很少被使用(Cuzick et al, 2008)。因此,發展低成本、高性能的測試將能改善發展中國家的衛生水準。

方法:重新思考研究優先次序與結果

在設計一個新的診斷技術上,NANO-MUBIOP方案優先考量能鼓勵資源少的各地區所採用之特性,例如拉丁美洲、加勒比地區、非洲撒哈拉以南地區、美拉尼西亞、南亞、中亞和東南亞等地區。它所包括的技術特點——例如對特定流行病學和致癌的不同類型HPV之間予以區分的能力——以及實用及後勤補給的特性——例如低開銷成本和簡單的操作。

性別化創新:

開發低成本的HPV篩檢測試。NANO-MUBIOP尋求開發廉價的HPV檢測平台。

透過性別化創新方法的應用前景以增加未來研究的潛在價值

-

確定NANO-MUBIOP平台的潛在用戶

-

了解子宮頸癌篩檢不良覆蓋率的原因

議題

背景:歐盟架構計畫7為診斷性應用而強化奈米科技多工性生物測定平台的敏感度,以及目前打擊子宮頸癌的策略

性別化創新 1:發展低成本的HPV篩檢測驗

透過性別化創新方法之應用,如何在未來研究中加入潛在價值

所增加的潛在價值 1:指明潛在使用者

方法:交織性研究方法

所增加的潛在價值 2:了解子宮頸癌篩檢效果不佳的原因

方法:重新思考研究優先次序與結果

結論

議題

目前已知約有四十種類型的人類乳突病毒(HPV)會感染生殖道(Trottier et al. 2009)。其中,有13種被證實為「高風險型」,容易引起子宮頸癌(Bhatla et al. 2010; Munoz et al. 2003。人類乳突病毒(HPV)的感染估計佔子宮頸癌原因的百分之百,同時也影響其他癌症發生率,特別是男性的陰莖癌、女性的外陰癌、以及男女都會得的肛門癌與多種類型的口腔癌(WHO, 2008b)。

世界衛生組織(WHO)強調篩檢的重要性並聲明,HPV疫苗的引進不應該壓制或分轉了有效子宮頸癌篩檢的經費(WHO, 2009)。近來在印度和中國所執行的研究表明,負擔得起的HPV DNA檢測能顯著降低晚期侵襲性子宮頸癌的發生率,以及在資源不足地區的死亡率(Sankaranarayanan et al. 2009; Qiao et al. 2008)。正如其它篩檢計畫一樣,該注意的是,NANO-MUBIOP尋求研發出一個檢測的平台,而這些檢測本身既不能預防也不能治療HPV病毒。

背景

歐盟架構計畫7為診斷性應用而強化奈米科技多工性生物測定平台(NANO-MUBIOP)的敏感度,以及強化目前打擊子宮頸癌的策略。

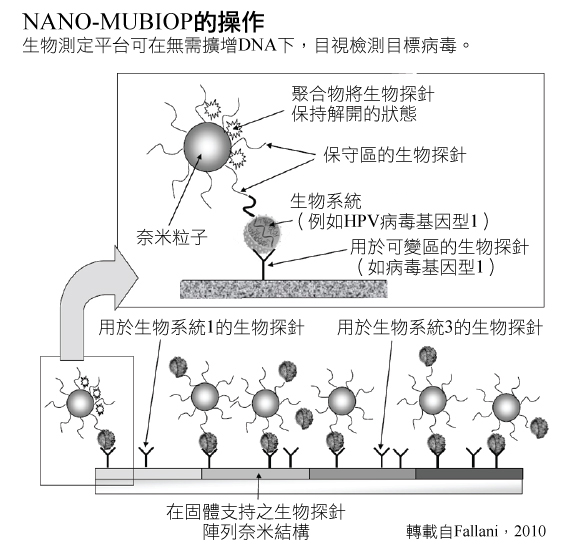

NANO-MUBIOP計畫尋求建立生物檢測,運用了奈米粒子技術,可以在無須放大DNA條件下運用來偵測一種目標病毒(比如HPV)。這個平台在早期階段中,被規劃成一種異質性的生物檢測方法,運用針對不同目標DNA的DNA探針。探針被安置在一個固態基質上(如玻片)。這些玻片被暴露在含有DNA的分析物中,在羧基二氧化矽奈米粒子的環境下這些奈米粒子會與DNA序列互補的探針一起作用於所有生物目標DNA(Fallani, 2010; Toth et al. 2912)。奈米粒子和DNA分析物相互結合,能促進並穩定DNA與基質上探針的結合。奈米粒子將可以用光學來檢測——可參考右側顯示NANO-MUBIOP如何運作之架構圖解。

生物樣本是直接可被NANO-MUBIOP平台所分析,無須事先經由聚合酶鏈反應(PCR)或其他方式來放大。在特定區域中,運用不同型態的探針於基質上,能夠辨識多重的目標DNA – 比如,在特定HPV類型中的相異DNA序列(Toth et. al. 2011; Liguri et. al, 2010)。

全面性子宮頸癌管理包括了篩檢,可藉由NANO-MUBIOP來實施。篩檢是主要的關鍵,因為早期發現的話,子宮頸癌是高度可治療的。在資源比較豐富的國家,子宮頸癌通常可以提早被檢測出來並早期治療,存活率比資源匱乏的國家要來得更高。因為在後者,子宮頸癌通常較晚發現,因而延遲治療甚至已無法治療(Perkin et. al. 2006)。目前已有許多可運用的篩檢測驗。左邊的圖表顯示了NANO-MUBIOP如何緊緊關連著子宮頸癌的預防和篩檢——可點擊進入查看。

性別化創新 1:發展低成本的HPV篩檢測驗

NANO-MUBIOP 研究者努力地想要發展出一種比較不貴的HPV測驗。目前雖能測試HPV,但因成本昂貴和高複雜度而限制了測驗的運用。因此,NANO-MUBIOP想要提供以下的改革:

-

低成本,不論就單次測驗,或對需要分配和施行測驗的基礎結構的經常花費而言(Trisolini et. al. 2008a)。

-

特別是相較於細胞學和DNA方法,NANO-MUBIOP對設備和操作員技術的要求降到最低,即便掃描或判讀系統仍是必須的 (Trisolini et.al. 2008a)。

-

特別是被拿來對比於其他DNA測試方法時,提供最快速的測試結果(Trisolini et. al. 2008a)。

-

有能力區別特殊的HPV類型(Trisolini et. al. 2008a)。

-

有能力測試來自男性與女性的樣本(Fallani, 2010) 。

透過性別化創新方法之應用,如何在未來研究中加入潛在價值

所增加的潛在價值 1:指明潛在使用者

研究者可能需要分析與生理/社會性別交織的因子,以指明潛在的NANO-MUBIOP使用者,然後是根據目標群體的需求,重新思考研究優先次序與結果以進行設計。

方法:交織性研究方法

雖然HPV在全世界的女人及男人中都導致了罹病和死亡,但是與HPV相關的疾病仍根據生理性別和地理區域而相當分佈不均:

以生理性別或類型來區分的HPV相關疾病: 大部分以HPV歸因的癌症約有94%都發生在女性身上,因為HPV會引發子宮頸癌的比例比其他類型的癌症還高(WHO, 2008b)。

圖表以Parkin等人(2006)的資料來產生。

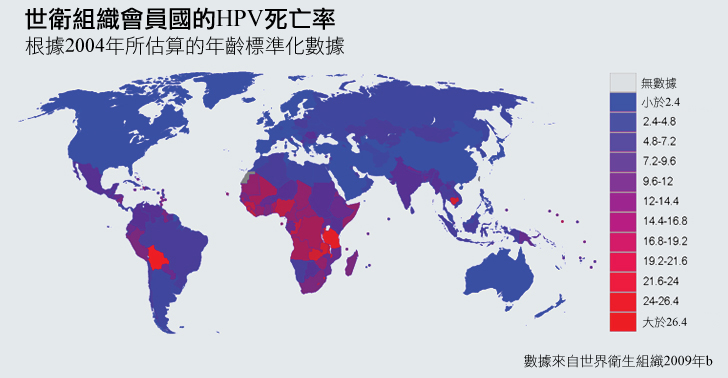

以地域來區分的HPV相關疾病: 大部分HPV歸因的癌症約有83%發生在發展中國家 (Parkin et al. 2006)。子宮頸癌造成的死亡特別集中在資源貧乏的地區:

所增加的潛在價值 2:了解子宮頸癌篩檢效果不佳的原因

NANO-MUBIOP 研究者尋找發展一種可以運用在發展中國家的HPV篩檢平台 (Trisolini et. al. 2008a)。了解這種使用者群體的需求可能需要一個更深入的方法—詳見如下。

方法:重新思考研究優先次序與結果

子宮頸癌篩檢效果可藉由四種特殊創新來加強:

為了增加可及性而降低成本: 子宮頸癌篩檢在已開發國及發展中國家都有高成本效益——也就是說,相較於許多其他醫療介入,拯救每一存活人年的單位成本是很低的(WHO, 2011; Goldhaber-Fiebert et al. 2008)。然而,成本要被發展中國家接受仍有障礙;在貧窮國家中的女性相較於富裕國家,則更不可能接受篩檢(Gakidou et al. 2008)。

子宮頸癌篩檢----不管是否經由光學方法、細胞學方法、或HPV檢測 ---- 其成本皆與人力、「可棄式供給品」(消耗品),以及「配備和實驗室使用」有關(儀表和基礎建設) (Goldie et al. 2005)。NANO-MUBIOP 研究者正尋求在三種地方減低成本,以創造一種不需要技術勞工(如細胞學測試般的)進行操作,以及不需要通過繁複的分子生物學實驗室進行 (如HPV的DNA測試常做的放大技術) (Trisolini et al. 2008a)。

促進品質控制的自動化測試: 在有子宮頸癌篩檢的國家中,低品質的篩檢服務會危及健康照護。在發展中國家,大約有45%的婦女可取得某種形式的子宮頸癌篩檢,但只有19%的女人接受的篩檢服務是有效的(Gakidou et al. 2008)。品質控制對以細胞學為基礎的測試(子宮抹片檢查和液態細胞學檢查)來說,特別具有挑戰性。細胞學篩檢的勞力密集特性,以及判讀檢測結果所需的廣泛訓練,都可能在實質上危及篩檢品質(Cuzick et al. 2008)。NANO-MUBIOP研究者目標在於,引進自動化測試來克服這些障礙(Trisolini et al. 2008c)。

加快測驗能允許快速的後續追蹤: 傳統的子宮頸癌篩檢計畫——特別是那些奠基在細胞學和HPV的DNA測試上的計畫——可能需要較長的後續追蹤時間。後續追蹤率經常很低,特別是在通訊及交通基礎建設都極為有限的發展中國家更是如此(Bosch et al. 2008)。

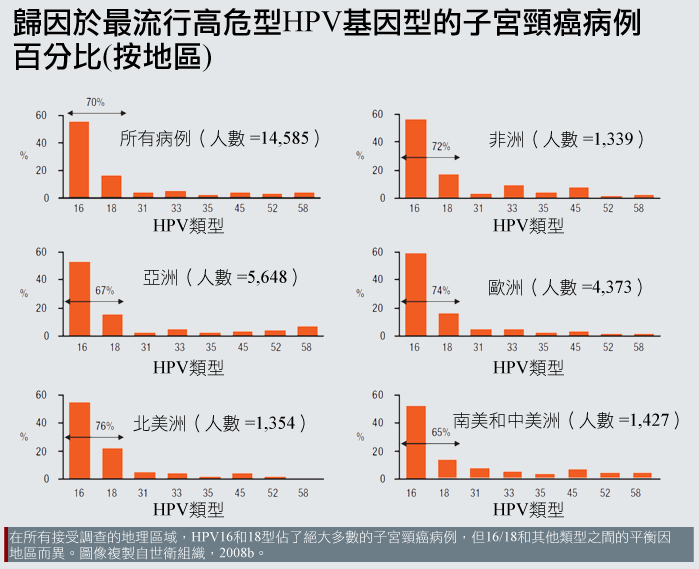

辨明HPV亞型可增強特殊性: 就全世界來說,由特定HPV類型病毒所引發的子宮頸癌負荷有些許差異。例如,HPV類型16以及類型18造就了北美地區76%的發病比例,但在中南美洲只有造成65%的個案,而在其他地區的致病率大約居於中間值:

所觀察到的類型盛行率(type-prevalence)差異原因尚未完全了解(Clifford et al, 2005)。其中的一些可能性包括:

免疫遺傳學:不同地理區域的人可能會有不同的遺傳多態性,遂而影響其等對特定HPV類型的易感性或抵抗(Hildesheim et al., 2002)。

其他傳染疾病盛行率:非HPV感染性疾病可能會影響特定HPV類型感染的風險。例如,HIV相關的免疫缺陷引發HPV-16感染的風險小於它引發感染其它HPV類型的風險(Strickler et al., 2003)。這也許可以解釋為什麼非洲(HIV相對盛行)和歐洲(HIV較不盛行)相比,HPV-16以外的HPV類型是更重要的子宮頸癌原因(Clifford et al., 2005)。

非傳染性疾病和其他情況的盛行率:營養不良可能導致資源貧乏地區較高的非HPV-16型發生率(Clifford et al., 2005)。

不管致病原因,世面上流行的HPV類型之異質性強調了NANO-MUBIOP測驗作為偵測多重類型的潛在用處。

除了盛行率的地理差異之外,不同類型的HPV也傾向於造成不同型態的子宮頸癌(Dahlstrom et al. 2010)。例如,比起其他病毒類型,「HPV-18通常與難以偵測或觀察的子宮頸內通道病灶有關」(Cuzil et al. 2008)。就致病原因來說,HPV類型的檢測具有潛在的治療價值,而NANO-MUBIOP研究者也已將多工性視為發展的首要順位(Trisolini et al. 2008a)。

結論

NANO-MUBIOP計畫已經指出HPV測試在已發展及發展中國家的關鍵需求。雖然還在研發中,NANO-MUBIOP計畫尋求生產一種測試,可以在女人及男人中有效並快速地偵測出HPV病毒,並且集中在運用自動化偵測以減低高額的人事花費。NANO-MUBIOP研究者已經研發出許多實驗室原型了,但這個平台在可行的臨床運用前,仍有許多工作尚待完成(Fallani, 2010)。

參考資料

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious diseases (2012). HPV vaccine recommendations. Pediatrics, 129 (3), 602-605.

Arbyn, M., Weiderpass,. E., & Capocaccia, R. (2012). Effect of Screening on Deaths from Cervical Cancer in Sweden. British Medical Journal, 344, e804.

Arbyn, M., Castellsagué, X., De Sanjosé, S., Bruni, L., Saraiya, M., Bray, F., & Ferlay, J. (2011). Worldwide Burden of Cervical Cancer in 2008. Annals of Oncology, 22 (12), 2675-2686.

Arbyn, M., Anttila, A., Jordan, J., Ronco, G., Schenck, U., Segnan, N., Wiener, H., Herbert, A., & Von Karsa, L. (2010). European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening, Second Edition—Summary Document. Annals of Oncology, 21 (3), 448-458.

Arbyn, M., Raifu, A., Weiderpass, E., Bray, F., & Anttila, A. (2009). Trends of Cervical Cancer Mortality in the Member States of the European Union. European Journal of Cancer, 45 (15), 2640-2648.

Bernard, H., Burk, R., Chen, Z., Van Doorslaer, K., Zur Hausen, H., & De Villiers, E. (2010). Classification of Papillomaviruses (PVs) Based on 189 PV Types and Proposal of Taxonomic Amendments. Virology, 401 (1), 70-79.

Bhatla, N., Classen, M., Denny, L., Fagan, J., Franceschi, S., Gueye, S., Jalloh, M., Mohammed, Z., Ngoma, T., Niang, L., Prinz, C., Quek, S., Torode, J., Wiersma, S., Wittet, S., You, W., & Hausen, H. (2010). Protection Against Cancer-Causing Infections - World Cancer Campaign 2010. Geneva: International Union Against Cancer (UICC).

Castellsagué, X., De Sanjosé, S., Aguado, T., Louie, K., Bruni, L., Muñoz, J., Diaz, M., Irwin, K., Gacic, M., Beauvais, O., Albero, G., Ferrer, E., Byrne, S., & Bosch, F. (2007). HPV and Cervical Cancer in the World: 2007 Report. Vaccine, 25 (S3), 1-241.

Castellsagué, X., & Muñoz N. (2003). Chapter 3: Cofactors in Human Papillomavirus Carcinogenesis—Role of Parity, Oral Contraceptives, and Tobacco Smoking. Journal of the National Cancer Institute: Monographs, 20 (31), 20-28.

Chin-Hong, P., Berry, J., Cheng, S., Catania, J., Da Costa, M., Darragh, T., Fishman, F., Jay, N., Pollack, L., & Palefsky, J. (2008). Comparison of Patient- and Clinician-Collected Anal Cytology Samples to Screen for Human Papillomavirus–Associated Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149 (5), 300-306.

Chin-Hong, P., Vittinghoff, E., Cranston, R., Buchbinder, S., Cohen, D., Colfax, G., Da Costa, M., Darragh, T., Hess, E., Judson, F., Koblin, B., Madison, M., & Palefsky, J. (2004). Age-Specific Prevalence of Anal Human Papillomavirus Infection in HIV-Negative Sexually Active Men Who Have Sex with Men: The EXPLORE Study. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 190 (12), 2070-2076.

Clifford, G., Gallus, S., Herrero, R., Muñoz, N., Snijders, P., Vaccarella, S., Anh, P., Ferreccio, C., Hieu, N., Matos, E., Molano, M., Rajkumar, R., Ronco, G., De Sanjosé, S., Shin, H., Sukvirach, S., Thomas, J., Tunsakul, S., Meijer, C., & Franceschi, S. (2005). Worldwide Distribution of Human Papillomavirus Types in Cytologically Normal Women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV Prevalence Surveys: A Pooled Analysis. The Lancet, 366 (9490), 991-998.

Cuzick, J., Arbyn, M., Sankaranarayanan, R., Tsu, V., Ronco, G., Mayrand, M., Dillner, J., & Meijer, C. (2008). Overview of Human Papillomavirus-Based and Other Novel Options for Cervical Cancer Screening in Developed and Developing Countries. Vaccine, 26 (S10), K29-K41.

Dahlström, L., Ylitalo, N., Sundström, K., Palmgren, J., Ploner, A., Eloranta, S., Sanjeevi, C., Andersson, S., Rohan, T., Dilner, J., Adami, H., & Sparén, P. (2010). Prospective Study of Human Papillomavirus and Risk of Cervical Adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Cancer, 127 (8), 1923-1930.

Denny, L., Quinn, M., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2006). Chapter 8: Screening for Cervical Cancer in Developing Countries. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S71-S77.

Denny, L., Kuhn, L., De Souza, M., Pollack, A., Dupree, W., & Wright, T. (2005). Screen-and-Treat Approaches for Cervical Cancer Prevention in Low-Resource Settings: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294 (17), 2173-2181.

De Vuyst, J., Clifford, G., Li, N., & Franceschi, S. (2009). HPV Infection in Europe. European Journal of Cancer, 45 (15), 2632-2639.

Dunne, E., Unger, E., Sternberg, M., McQuillan, G., Swan, D., Patel, S., & Markowitz, L. (2007). Prevalence of HPV Infection among Females in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297 (8), 813-819.

Dunne, E., Nielson, C., Stone, K., Markowitz, L., & Giuliano, A. (2006). Prevalence of HPV Infection among Men: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 194 (8), 1044-1057.

Fallani, M. (2010). Periodic Report - NANO-MUBIOP (Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications). Brussels: Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS). PDF.

Franceschi, S., Herrero, R., Clifford, G., Snijders, P., Arslan, A., Anh, P., Bosch, F., Ferreccio, C., Hieu, N., Lazcano-Ponce, E., Matos, E., Molano, M., Qiao, Y., Rajkumar, R., Ronco, G., De Sanjosé, S., Shin, H., Sukvirach, S., Thomas, J., Meijer, C., & Muñoz, N. (2006). Variations in the Age-Specific Curves of Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women Worldwide. International Journal of Cancer, 119 (11), 2677-2684.

Franco, E., Mahmud, S., Tot, J., Ferenczy, A., & Coutlée, F. (2009). The Expected Impact of HPV Vaccination on the Accuracy of Cervical Cancer Screening: The Need for a Paradigm Change. Archives of Medical Research, 40 (6), 478-485.

Gakidou, E., Nordhagen, S., & Obermeyer, Z. (2008). Coverage of Cervical Cancer Screening in 57 Countries: Low Average Levels and Large Inequalities. Public Library of Science (PLoS) Medicine, 5 (6), e132.

García-Closas, R., Castellsagué, X., Bosch, X., & González, C. (2005). The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Cervical Carcinogenesis: A Review of Recent Evidence. International Journal of Cancer, 117 (4), 629-637.

Giuliano, A., Lu, B., Nielson, C., Flores, R., Papenfuss, M., Lee, J., Abrahamsen, M., & Harris, R. (2008). Age-Specific Prevalence, Incidence, and Duration of Human Papillomavirus Infections in a Cohort of 290 US Men. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 198 (6), 827-835.

Giuliano, A., Sedjo, R., Roe, S., Harris, R., Baldwin, S., Papenfuss, M., Abrahamsen, M., & Inserra, P. (2002). Clearance of Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection: Effect of Smoking (United States). Cancer Causes and Control, 13 (9), 839-846.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). (2012). CERVARIX Full Prescribing Information. Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: GSK. PDF.

Goldhaber-Fiebert, J., Stout, N., Salomon, J., Kuntz, K., & Goldie, S. (2008). Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening with Human Papillomavirus DNA Testing and HPV-16,18 Vaccination. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100 (5), 308-320.

Goldie, S., Gaffikin, L., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J., Gordilo-Tobar, A., Levin, C., Mahé, C., & Wright, T. (2005). Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening in Five Developing Countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 353 (20), 2158-2168.

Gorgos, L., & Marrazzo, J. (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections among Women who Have Sex with Women. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53 (S3), S84-S91.

Gustaffson, L., Pontéén, J., Zack, M., & Adami, H. (1997). International Incidence Rates of Invasive Cervical Cancer after Introduction of Cytological Screening. Cancer Causes and Control, 8 (5), 755-763.

Hildesheim, A., & Wang, S. (2002). Host and Viral Genetics and Risk of Cervical Cancer: A Review. Virus Research, 89 (2), 229-240.

Howard M., Lytwyn, A., Redwood-Campbell, L., Fowler, N., & Karwalajtys T. (2009). Barriers to Acceptance of Self-sampling for Human Papillomavirus across Ethnolinguistic Groups of Women. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 100 (5), 365-369. Howard, M., Sellors, J., Kaczorowski, J., & Lörincz, A. (2004). Optimal Cutoff of the Hybrid Capture II Human Papillomavirus Test for Self-Collected Vaginal, Vulvular, and Urine Specimens in a Coloposcopy Referral Population. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 8 (1), 33-37.

Joura, E., Kjaer, S., Wheeler, C., Sigurdsson, K., Iversen, O., Hernandez-Avila, M., Perez, G., Brown, D., Koutsky, L., Tay, E., Garc í a, P., Ault, K., Garland, S., Leodolter, S., Olsson, S., Tang, G., Ferris, D., Paavonen, J., Lehtinen, M., Steben, M., Bosch, X., Dillner, J., Kurman, R., Majewski, S., Muñoz, N., Myers, E., Villa, L., Taddeo, F., Roberts, C., Tadesse, A., Bryan, J., Lupinacci, L., Giacoletti, K., Lu, S., Vuocolo, S., Hesley, T., Haupt, R., & Barr, E. (2008). HPV Antibody Levels and Clinical Efficacy Following Administration of a Prophylactic Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine. Vaccine, 26 (52), 6844-6851.

Kuo, H., & Fujise, K. (2011). Human Papillomavirus and Cardiovascular Disease Among U.S. Women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2006. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58 (19), 2001-2006. Liguri, G., & Trisolini, F. (2010). High Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Method and Device. United States Patent Application 0240147-A1. September 23.

Markowitz, L., Sternberg, M., Dunne, E., McQuillan, G., & Unger, E. (2009). Seroprevalence of Human Papillomavirus Types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 205 (7), 1059-1067.

Mayr, N., Small, W., & Gaffney, D. (2011). Cervical Cancer. In Lu, J., & Brady, L. (Eds.), Decision Making in Radiation Oncology, pp. 661-710. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Melnikow, J., McGahan, C., Sawaya, G., Ehlen, T., & Coldman, A. (2009). Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Outcomes After Treatment: Long-term Follow-up From the British Columbia Cohort Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 101 (10), 721-728.

Merck & Company. (2012). GARDASIL Full Prescribing Information. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck & Company. PDF.

Mitchell S., Ogilvie, G., Steinberg, M., Sekikubo, M., Biryabarema, C., & Money, D. (2011). Assessing Women's Willingness to Collect their Own Cervical Samples for HPV Testing as Part of the ASPIRE Cervical Cancer Screening Project in Uganda. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 114 (2), 111-115.

Muhlstein, J. (2011). Chronic Infection and Coronary Atherosclerosis: Will the Hypothesis Ever Really Pan Out? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58 (19), 2007-2009.

Muñoz, N., Castellsagué, X., De González, A., & Gissmann, L. (2006). Chapter 1: HPV in the Etiology of Human Cancer. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S1-S10.

Muñoz, N., Bosch, X., De Sanjosé, S., Herrero, R., Castellsagué, X., Shah, K., Snijders, P., & Meijer, C. (2003). Eipdemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 348 (6), 518-527.

Nantunen, K., Lehtinen, J., Namujju, P., Sellors, J., & Lehtinen, M. (2011). Aspects of Prophylactic Vaccination against Cervical Cancer and Other Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancers in Developing Countries. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Article ID 675858.

Palefsky J. (2008) Human Papillomavirus and Anaöl Neoplasia. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 5 (2), 78-85.

Palefsky, J., Fillison, M., & Strickler, H. (2006). Chapter 16: HPV Vaccines in Immunocompromised Women and men. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S140-S146.

Parkin, D. (2011). Cancers Attributable to Exposure to Hormones in the UK in 2010. British Journal of Cancer, 105 (S2), S42-S48.

Parkin, D., & Bray, F. (2006). Chapter 2: The Burden of HPV-Related Cancers. Vaccine, 24 (3), S11-S25.

Petry, K., Scheffel, D., Bode, U., Gabrysiak, T., Köchel, H., Kupsch, E., Glaubitz, M., Niesert, S., Kühnle, H., & Schedel, I. (1994). Cellular Immunodeficiency Enhances the Progression of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cervical Lesions. International Journal of Cancer, 57 (6), 836-840.

Schiffman, M., & Adrianza, M. (2000). Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS) - Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) Triage Study: Design, Methods, and Characteristics of Trial Participants. Acta Cytologica, 44 (5), 726-742.

Shoveller, J. A., Knight, R., Johnson, J., Oliffe, J. L. & Goldenberg S. (2010). 'Not the swab!' Young men's experiences with STI testing. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32 (1), 57–73.

Smith, J., Green, J., De Gonzalez, A., Appleby, P., Peto, J., Plummer, M., Franceschi, S., & Beral, V. (2003). Cervical Cancer and Use of Hormonal Contraceptives: A Systematic Review. The Lancet, 361 (9364), 1159-1167.

Strickler, H., Palefsky, J., Shah, K., Anastos, K., Kelin, R., Minkoff, H., Duerr, A., Massad, L., Celentano, D., Hall, C., Fazzari, M., Su-Uvin, S., Bacon, M., Schuman, P., Levine, A., Durante, A., Gange, S., Melnick, S., & Burk, R. (2003). Human Papillomavirus Type 16 and Immune Status in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Seropositive Women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 95 (14), 1062-1071.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2012). Mathematical Modeling and Computer Simulation of Brownian Motion and Hybridization of Nanoparticle-Bioprobe-Polymer Complexes in the Low Concentration Limit. Molecular Simulation, 38 (1), 66-71.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2011). 3D Brownian Motion Simulator for High-Sensitivity Nano-Biotechnological Applications. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Transactions of Nanobioscience, 10 (4), 248-249.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2010). Mathematical Modeling and Computer Simulation of Brownian Motion and Hybridization of Nanoparticle-Bioprobe-Polymer Complexes in the Low Concentration Limit. Nanotech, 3, 161-164.

Trottier, H., & Burchell, A. (2009). Epidemiology of Mucosal Human Papillomavirus Infection and Associated Diseases. Public Health Genomics, 12 (5-6), 291-307.

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008a). NANO-MUBIOP: About the Project..

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008b). NANO-MUBIOP: HPV in the Developing Countries.

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008c). NANO-MUBIOP: Expected Outcomes.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2011). Screening is Still the "Best Buy" for Tackling Cervical Cancer. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89 (9), 621-700.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Handbook of Cancer Prevention, Volume 10: Cervix Cancer Screening. Geneva: IARC.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009a). Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: WHO Position Paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record, 15 (84), 117-132.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009b). Death and Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) Estimates by Cause for WHO Member States—Persons, All Ages. Geneva: WHO. XLS

World Health Organization (WHO). (2008a). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Background Paper. Canberra: Biotext Proprietary Company, Limited.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2008b). Cervical Cancer, Human Papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV Vaccines: Key points for Policy-Makers and Health Professionals. Geneva: WHO. World Health Organization (WHO). (2006). Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002a). Cervical Cancer Screening in Developing Countries. Geneva: WHO Programme on Cancer Control, Department of Reproductive Health and Research.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002b). Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking: Summary of Data Reported and Evaluation. Geneva: WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Waller, J., McCaffery, K., Forrest, S., & Wardle, J. (2004). Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer: Issues for Biobehavioral and Psychosocial Research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27 (1), 68-79.

Wright, T., Denny, L., Kuhn, L., Pollack, A., & Lorincz, A. (2000). HPV DNA Testing of Self-Collected Vaginal Samples Compared with Cytologic Screening to Detect Cervical Cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283 (1), 81-86.

本性別化創新方案係應歐盟委員會要求對其框架計劃7中的幾個項目進行分析。「增強基於奈米多重性技術生物測定平台於診斷應用的靈敏度」(NANO-MUBIOP)方案旨在開發一種低成本的HPV篩檢測試。我們對性別化創新以及分析生理性別和社會性別的方法予以確定,並透過性別化創新指出了潛在的「增值」可能性。

性別化創新:

大約有40種已知感染生殖道的HPV。HPV感染所引起的子宮頸癌病例估計為100%,並會影響男性特異性癌症(如陰莖癌)、女性特異性癌症(如外陰癌),和男性和女性癌症(肛門癌和數種類型的口腔癌)的發病率。

NANO-MUBIOP正在開發一種成本低廉的HPV檢測。目前已有的HPV檢測成本高、且操作複雜,因此採用量相當有限。

透過性別化創新方法的應用前景以增加未來研究的潛在價值:

NANO-MUBIOP尋求開發能在開發中國家使用的HPV檢測平台。了解此用戶群的需求可能需要交織性研究方法和重新思考研究優先次序與結果。據估計,有83%HPV-類型癌症發生在發展中國家。在設計一個新的診斷技術上,NANO-MUBIOP方案優先考量能鼓勵資源少的各地區所採用之特性,例如拉丁美洲、加勒比地區、非洲撒哈拉以南地區、美拉尼西亞、南亞、中亞和東南亞等地區。