動物研究:

健康和生物醫學研究設計

議題

多數動物研究以雄性為主並排除雌性動物 (Zucker et al., 2010; Marts et al., 2004),而這將引起三項問題:

- 與女性相關的疾病發展知識會因為雌性動物利用不足而減少。 雄性動物的研究結果常被同時解讀成雌性動物結果而忽略需根據生理性別而做的調整。即使某些情況較常見於雌性動物,多數研究仍使用雄性動物。雌性動物用於試驗的比例與實際女性病患的罹病比例仍有一段差距。

- 無法於基礎生物研究將生理性別列為變數(Holdcroft, 2007)。然而,許多個案已證實生理性別為重要變數。例如:免疫功能的調控。

- 錯失調查與疾病發展有相互作用之女性特有現象的機會 (例如:懷孕期與某些物種特有的停經期)。基於試驗對懷孕婦女安全性的影響,模式生物之懷孕研究就變得特別重要。

方法:實驗室動物研究

國家一般都通過立法,要求政府資助的人體研究必須包含女性受測者。舉例來說,美國國家衛生研究院要求所有人類受測者的研究皆須包含「女性和少數族裔的成員以及他們的亞群」(雖然只有第三期臨床試驗要求有足夠的女性代表以進行生理性別分析)(參見:重大政策實施時間表)。然而,即使兩性動物研究與各種荷爾蒙研究的新發現皆顯示會影響藥物開發與病人照護,這些指導方針仍很少應用於動物研究。

性別化創新

- 研究動物模式的生理性別差異已經促使新的創傷性腦損傷(TBI,常見於男性多於女性)治療法問世。

- 以動物模式說明懷孕、動情週期以及更年期狀態可以顯示荷爾蒙對基礎分子路徑的生物影響,也對某些自體免疫疾病的瞭解至關重要。

- 調控因素已為了改善動物模式的毒性反應而考量生理性別差異;並且導致更有力的環境衛生標準。

議題

雌性動物被低度呈現

性別化創新 1:生理性別研究促使新的創傷性腦損傷治療法問世

方法:分析生理性別

方法:實驗室動物研究

性別化創新 2:配合動情週期以及停經期的取樣方式可以提升免疫系統的基本知識

性別化創新 3:加強環境衛生標準

方法:重新思考標準和參考模型

歐盟訂定之標準與參考模型

美國訂定之標準與參考模型

結論

下一步

議題

自西方科學與醫學發展開始,以動物模式進行研究就至關重要。然而,直到1960年代,除了生殖相關的研究外,用於研究的動物生理性別鮮少被報導。即使至今,「在神經科學、生理學以及跨領域生物學期刊中,仍有百分之二十二至四十二的文章忽略」受試動物的生理性別 (Beery et al., 2011)。

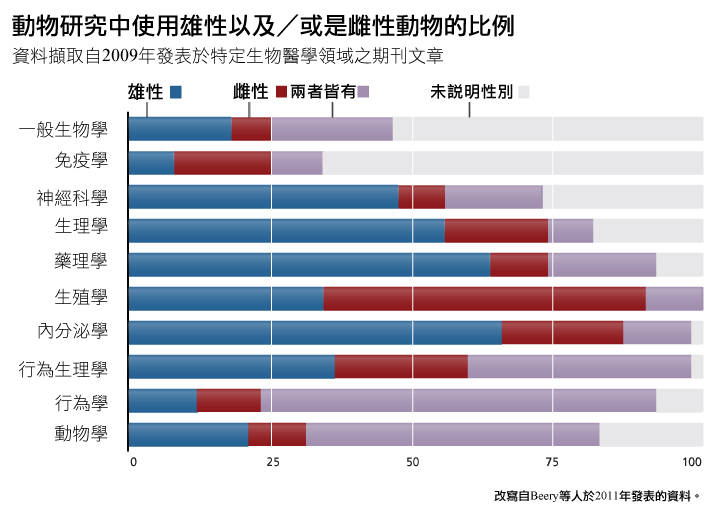

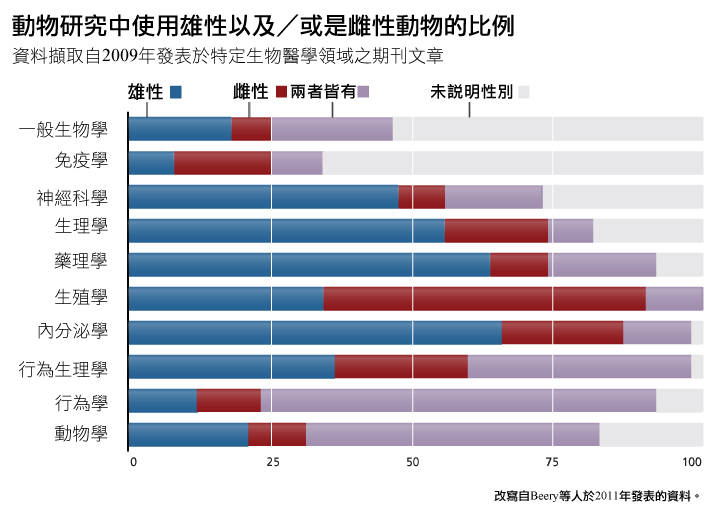

那些有報導動物生理性別的研究分析顯示,除生殖生物學與免疫學外,雌性動物於多數次領域的代表性仍顯不足,參見下圖。

雌性動物被低度呈現

研究人員可能進行單一生理性別動物研究,以減少實驗成本或是希望降低研究結果的變異性(McCarthy et al., 2002)。單一生理性別實驗是研究特定生理性別專屬現象的唯一選擇(例如:卵巢癌或前列腺癌)。而且若其中一個生理性別已被替補,或是有力的證據顯示生理性別對研究結果並無影響,單一生理性別研究仍屬有益。然而,多數單一生理性別動物研究並不屬於這些範疇。在對兩性都會造成影響的狀況,以及有證據顯示生理性別會影響結果的研究中,雌性動物都被低度呈現。

研究人員會避免使用雌性動物,因為在動情週期中持續波動的荷爾蒙濃度會和實驗結果產生交互作用(Becker et al., 2005; Wizemann et al., 2001)。少數情況下,研究人員會避免使用雄性動物,因為某些品種或品系的雄性動物會彼此攻擊,使得籠養變得困難(Gatewood et al., 2006)。由於雌性大鼠對某些毒物非常敏感,因此毒理學研究偏好使用雌性大鼠 (European Commission, 2008)。

性別化創新 1:生理性別研究促使新的創傷性腦損傷治療法問世

創傷性腦損傷不論於歐洲(主要原因為汽車碰撞)或美國(主要原因為槍傷;Tagliaferri et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2000; Roof et al., 2000)皆常見於男性多於女性。包含雌性動物的新創傷性腦損傷研究可以進行精緻的生理性別分析,並為創傷性腦損傷病患製造創新的治療法(見方法)。

方法:分析生理性別

分析生理性別始於研究人員同時用兩種生理性別之動物於實驗中,並分析資料以決定雌性或雄性動物的研究結果是否不同。於創傷性腦損傷動物模式中,雌性動物持續顯示其結果較雄性動物佳。因此,雌性為「最受保護」的生理性別,而雄性則為「影響最大」的生理性別。這個差異適用於其他物種或各種近親與遠親交配的小鼠品系 (Hurn et al., 2005)。

一旦觀察到生理性別差異,進一步的實驗便可釐清造成這些差異的機制 (Grove et al., 2010)—參見下列方法。

方法:實驗室動物研究

決定生理性別差異是否存在需要考量雌性動物的動情週期,若動情週期未在考量範圍內,也就是將整個週期的平均結果做為研究結果,則生理性別差異也許存在,但是無法被偵測到(Stoffel et al., 2003)。為確實評估生理性別差異,機制性研究是必要的,因為有時候特定藥物或其他介入可能經由不同機制於兩種生理性別動物模式皆產生相同的效果(Liu et al., 2007)。此外,諸多專屬於特定生理性別的差異可能會產生完全相反的效果並相互抵銷,因此反而無法觀察到生理性別差異(Palaszynski et al., 2005)。

如果從動物模式中觀察到生理性別差異,性荷爾蒙的影響測試就非常重要,這些測試可能包含:

- 於雌性動物不同的動情週期時間點取樣。具生育能力的動物中,有效力的研究設計包含監測雌性動物的動情週期。一個基礎的實驗設計可能涵蓋十組小鼠:兩組雄性小鼠(實驗組和控制組)以及八組雌性小鼠(四天動情週期中的每一天,各有一組實驗組和控制組)。更簡單的選擇是單純地將雌性動物的動情週期分為兩部分:動情期與非動情期,然後再細分成實驗組和控制組 (Becker et al., 2005)。此外,由於某些哺乳動物會有同步排卵的現象,不同排卵時間的雌性動物在籠養時應避免近距離接觸,以免影響排卵日期 (Meziane et al., 2007)。

創傷性腦損傷動物模式中,動情週期對研究結果的影響並不大 (Wagner et al., 2004),但是其對免疫功能的研究便影響甚鉅 (參見下方性別化創新 2)。- 於雌性動物懷孕期或假懷孕期取樣。 創傷性腦損傷的研究人員取樣雄性大鼠、有正常循環週期的雌性大鼠以及有假懷孕特徵的雌性大鼠。結果發現,雄性大鼠的水腫情形最為嚴重,而有正常循環週期的雌性大鼠其水腫情況稍緩,其中有假懷孕特徵的雌性大鼠之水腫情形最輕微(Roof et al., 1993)。同時也發現黃體激素於雄性大鼠體內濃度最低,而有正常循環週期的雌性大鼠體內濃度稍高,並以有假懷孕特徵的雌性大鼠體內濃度最高。此結果暗示黃體激素可能有對抗水腫的保護功能(Meffre et al., 2007)。

- 人為操控荷爾蒙濃度。 在創傷性腦損傷的動物模式中,卵巢切除術會降低有完整卵巢之雌性大鼠具有的生存優勢。注射黃體激素可以部分恢復雌性大鼠因卵巢切除術喪失的生存優勢,並且增加雄性大鼠的存活率(Bayir et al., 2004)。

研究人員利用創傷性腦損傷動物模式得來的證據(透過分析生理性別和於不同荷爾蒙階段之雌性動物採樣所得之結果)設計適用於人類的實驗性治療。一項雙盲臨床研究顯示,在接受緊急創傷性腦損傷治療後隨即接受黃體激素之病患的死亡率較低,而且其神經功能的恢復也較控制組病患(有相同損傷)佳。此外,接受黃體激素的病患對此激素耐受性極佳(Xiao

et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2007)。未來需要更多研究以:

- 根據病患特性(例如:生理性別與年齡)和損傷特性進行之黃體激素治療法的危險性與益處之評估。

- 闡明黃體激素在創傷性腦損傷中保護病患大腦不受損傷的機制。

性別化創新 2:配合動情週期以及停經期的取樣方式可以提升免疫系統的基本知識

科學家藉由雌性小鼠的實驗結果發現性荷爾蒙對免疫系統功能相當重要。雌性小鼠於非動情期或動情期暴露於抗原後取樣的結果顯示,其脾臟的免疫反應與雄性的脾臟免疫反應類似。但是雌性小鼠於動情前期或動情後期接受抗原挑戰後取樣的結果顯示,其抗體數目比雄性的抗體數目多出三倍以上(Krzych et al., 1978)。若將這些差異與黃體激素和雌激素的濃度(這些激素濃度也會隨動情週期而有所變動)相連結將會揭開性荷爾蒙對免疫功能的影響(Bergman et al., 1992)。

停經動物模式雖仍處於發展階段(參見下列步驟),其已顯示與荷爾蒙一同變化的免疫特性。小鼠切除卵巢後會進入「急性停經期」,並有「降低淋巴球趨化性,促分裂原誘發T細胞增生反應以及[介白素2]之產生」的特徵顯現(Marriott et al., 2006)。

了解賀爾蒙與免疫功能和治療多種疾病相關,包括:自體免疫疾病與人類免疫缺乏病毒感染症。舉例來說,動物模式已被用來調查為何人類免疫缺乏病毒量在男性(比起女性)體內較快速增加(Meier et al., 2009)。

性別化創新 3:加強環境衛生標準

動物模式除了可用於基礎研究和臨床前試驗外,亦為化學物質毒性評測以及環境監測不可或缺的一環。歐盟委員會的衛生及消費者保護機構(IHCP)以及美國國家毒理學計畫中心(NTP)已分析參考模型,以便改善環境標準(見 方法)。

方法:重新思考標準和參考模型

在毒理學參考模型中考慮生理性別很重要:在某些個案中,某種化合物可能對雌性和雄性個體的影響有品質上的差異,特別是當此化合物是內分泌干擾素/環境荷爾蒙時(見案例研究:環境化學物質)。

衛生及消費者保護機構使用果蠅進行突變模型的「性聯隱性致死試驗」,以期能篩選出誘導突變活動之化學物質(European Commission, 2008)。

歐盟訂定之標準與參考模型

歐盟委員會的衛生及消費者保護機構(IHCP)對生理性別分析和取樣有相當嚴格的要求(European Commission, 2008):

- 需同時包含雌性與雄性動物。 舉例來說,在進行吸入性毒性測試時,研究人員需於每個濃度之測試裡使用相同數目的雌性與雄性動物。在其他測試中則偏好使用對毒性物質較為敏感的生理性別(通常是雌性)。

- 需報告研究受測者的生理性別。 不論是單一生理性別或多重生理性別實驗,衛生及消費者保護機構要求研究人員報告「實驗動物的數目、年齡和生理性別」。

- 需針對懷孕的雌性動物進行採樣以檢測發育毒性。 這項內容允許研究人員收集「關於產前暴露對懷孕測試動物與在子宮內發育之個體之影響的資訊」。

美國訂定之標準與參考模型

美國國家毒理學計畫中心(NTP)要求所有常規動物毒理學研究(NTP, 2006)皆需提供生理性別分析資料,亦即:

- 報告研究受測者的生理性別。 美國國家毒理部聲明「研究數據皆需製表呈現,而且需依物種、生理性別和治療組別排列」。

- 依生理性別分析結果並報告無效結果。 所有美國國家毒理部進行的分析皆有註記生理性別差異是否存在以及是否達統計顯著差異。

- 分析與生理性別相互影響的因子。 所有的分析皆需控制體重,因此體重差異才不會被誤解為生理性別差異。反之亦然。

結論

性別化創新:

- 生理和病理生理學: 納入雌性動物的實驗研究,導引出關於創傷性腦損傷的新知識,也因此有了新療法。生理性別和荷爾蒙狀態的取樣也產生新的關於免疫系統受荷爾蒙調節的知識,而這個新知識將與自體免疫疾病和感染的治療有關。這項資訊目前已可應用於開發疫苗的治療劑量(Klein et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2010)。

- 管制性政策: 分析生理性別已變成歐盟和美國共同努力瞭解、預防和管制環境汙染的重要目標。

下一步

-

未來研究需求應包含:

- 從細胞和組織層面分析生理性別差異。 基礎研究裡的生理性別分析主要源自於動物實驗,而此分析主要以荷爾蒙調節之生理性別差異為主。細胞培養或組織萃取實驗則鮮少分析或報告檢體的生理性別。一篇發表於高影響力與有同儕審查機制之心血管疾病期刊的文章指出,只有百分之20至28的文章描述使用之細胞檢體的生理性別。而在這些少數有報告生理性別的研究中,百分之69的細胞實驗只使用雄性動物的檢體(Taylor et al., 2011)。這種差異是值得關注的,因為新的研究顯示,細胞生理性別對幹細胞治療的發展相當重要 (見案例研究:幹細胞)。

- 分析與生理性別交織的因子,以避免過度強調生理性別差異。 並非所有在雌性與雄性動物、細胞、組織或男性與女性間觀察到的差異皆與生物生理性別有關。 分析與生理/社會性別交織的因子 對於避免過度強調生理性別差異的問題至關重要。這些重要因子包括:飲食、荷爾蒙濃度以及物種。出生後短暫來自母親的相互影響與行為的生理性別差異有關:大母鼠與雌性或雄性幼鼠的互動不同,因而產生行為發展的差異(Moore, 1992)。

- 建立停經動物模式。 高品質、高效度的停經動物模式是有需要的。雖然靈長類動物亦有類似停經期的過程,但使用靈長類的諸多挑戰以及老年雌性動物的缺乏,將成為研究的限制。實驗動物可藉由卵巢切除術的手術方式製造停經期,而這種方式可用來模擬人類女性於雙側卵巢切除術後的停經期,但是可能無法用來與自然發生之更年期女性相比(Bellino et al., 2003)。而用嚙齒類動物模擬人類停經期的策略則是給與小鼠或大鼠會誘發卵巢早期性衰竭的藥物,並使用基因轉殖小鼠(例如:Foxo3a-/-品系)以加速卵巢衰老(Wu et al., 2005)。

- 以動物模型研究社會性別差異。 將雌性與雄性動物置於不同的物理和社會環境對其行為和研究結果會有顯著影響。為了確認籠養系統以及照顧方式不會產生系統性誤差,社會性別分析是需要的(Holdcroft, 2007)。特別是如果研究人員預期會有特定的生理性別差異,他們照顧或籠養雌性與雄性動物的方式將可能不同;也就是他們可能會以特定方式處理以製造生理性別差異,或是選擇可能產生生理性別差異的特殊行為測驗(Birke, 2011)。飼養和處理方式可以決定動物的壓力程度,從而改變行為和生物化學數據(Beck et al., 2002)

-

下一步政策包括:

- 研究人員需報告受測者之生理性別。 在補助研究或發表研究結果前,審核機關以及期刊編輯可以要求研究人員報告研究受測者的生理性別。報告生物模式的生理性別可以避免研究結果不當廣義化,促使進行統合分析,以及顯示是否有某一生理性別的動物被忽略。目前主要的生物科學贊助者,包含英國醫學研究委員會(MRC)已要求研究人員報告研究動物的「物種、品系、生理性別、發展階段[…]以及體重等」。主要的期刊,包含 自然(Nature)和科學出版物的公共圖書館已經制訂相同的要求(National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement, and Reduction of Animals in Research 2008; Kilkenny et al., 2010)。

- 要求兩性研究以及生理性別分析。 政府機關可以在適當時機要求公家補助的研究要同時有兩種生理性別之受測者,以及要求每種生理性別其「樣本數應符合要求」。公家和私人補助機構皆可以有下列看法:「實驗包含雌性動物能增進實驗之科學價值,因而會影響實驗補助」(Beery et al., 2011)。

- 標準化「生理性別」和「社會性別」於動物研究的使用準則。 目前「生理性別」和「社會性別」這兩個術語在許多動物研究中都交替使用,也因而讓文獻搜尋和統合分析變得複雜。生理性別與社會性別是不同的名詞。把此兩術語的使用方式標準化,以「生理性別」表示雄性或雌性的生物特性,將可解決這項問題(Marts, 2004)。

參考資料

Bayir, H., Marion, D., Puccio, A., Wisniewski, S., Janesko, K., Clark, R., & Kochanek, P. (2004). Marked Gender Effect on Lipid Peroxidation after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Adult Patients. Journal of Neurotrauma, 21 (1), 1-8.

Becker, J., Arnold, A., Berkley, K., Blaustein, J., Eckel, L., Hampson, E., Herman, J., Marts,

S., Sadee, W.,

Steiner, M., Taylor, J., & Young, E. (2005). Strategies and Methods for Research on Sex

Differences in Brain and Behavior. Endocrinology, 146 (4), 1650-1673.

Beck, K., & Luine, V. (2002). Sex Differences in Behavioral and Neurochemical Profiles after

Chronic Stress: Role of Housing Conditions. Physiology and Behavior, 75 (5), 661-673.

Beery, A., & Zucker, I. (2011). Sex Bias in Neuroscience and Biomedical Research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35 (3), 565-572.

Bellino, F., & Wise, P. (2003). Nonhuman Primate Models of Menopause Workshop. Biology of Reproduction, 68 (1), 10-18.

Bergman, M., Schachter, B., Karelus, K., Combatsiaris, E., Garcia, T., & Nelson, J. (1992). Up-Regulation of the Uterine Estrogen Receptor and its Messenger Ribonucleic Acid during the Mouse Estrus Cycle: The Role of Estradiol. Endocrinology, 130 (4), 1923-1930.

Birke, L. (2011). Telling the Rat What to Do: Laboratory Animals, Science, and Gender. In Fisher, J. (ed.), Gender and the Science of Difference: Cultural Politics of Contemporary Science and Medicine, pp. 91-107. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

European Commission. (2008). Council Regulation EC-440-2008: Laying Down Test Methods Pursuant

to Regulation EC-1907-2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Registration,

Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH). Official Journal of the

European Union, 31 (5), 142-739.

Gatewood, J., Wills, A., Shetty, S., Xu, J., Arnold, A., Burgoyne, P., & Rissman, E. (2006).

Sex Chromosome

Complement and Gonadal Sex Influence Aggressive and Parental Behaviors in Mice. The Journal

of Neuroscience, 26 (8), 1335-2342.

Grove, K., Fried, S., Greenberg, A., Xiao, Z., & Clegg, D. (2010). A Microarray Analysis of

Sexual Dimorphism of Adipose Tissue in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obese Mice. International

Journal of Obesity, 34, 989-1000.

Holdcroft, A. (2007). Integrating the Dimensions of Sex and Gender into Basic Life Sciences Research: Methodologic and Ethical Issues. Gender Medicine, 4 (S2), S64-S74.

Hurn, P., Vannucci, S., & Hagberg, H. (2005). Adult or Perinatal Brain Injury : Does Sex Matter? Stroke, 36 (2), 193-195.

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W., Cuthill, I., Emerson, M., & Altman, D. (2010). Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments. Public Library of Science (PLoS) Biology, 8 (6), e1000412.

Klein, S., Passaretti, C., Anker, M., Olukoya, P., & Pekosz, A. (2010). The Impact of Sex, Gender, and Pregnancy on 2009 H1N1 Disease. Biology of Sex Differences, 1 (5), 1-12.

Krzych, U., Strausser, H., Bressler, J., & Goldstein, A. (1978). Quantitative Differences

in Immune Responses during

the Various Stages of the Estrus Cycle in Female BALB/c Mice. The Journal of Immunology, 121

(4), 1603-1605.

Liu, N., von Gizycki, H., & Gintzler, A. (2007). Sexually Dimorphic Recruitment of Spinal

Opioid Analgesic Pathways by the Spinal Application of Morphine. Journal of Pharmacology and

Experimental Therapeutics, 322 (2), 654-660.

Marriott, I., & Huet-Hudson, Y. (2006). Sexual Dimorphism in Innate Immune Responses to Infectious Organisms. Immunologic Research, 34 (3), 177-192.

Marts, S., & Keitt, S. (2004). Foreword: A Historical Overview of Advocacy for Research in Sex-Based Biology. Advances in Molecular and Cell Biology, 34, V-XIII.

McCarthy, M., & Becker, J. (2002). Neuroendocrinology of Sexual Behavior in the Female. In Becker, J., Breedlove, S., Crews, D., & McCarthy, M. (Eds.), Behavioral Endocrinology, pp. 124-132. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Meffre, D., Pianos, A., Liere, P., Eychenne, B., Cambourg, A., Schumacher, M., Stein, D., & Guennoun, R. (2007). Steroid Profiling in Brain and Plasma of Male and Pseudopregnant Female Rats after Traumatic Brain Injury: Analysis by Gas Chromatography / Mass Spectrometry. Endocrinology, 148 (5), 2505-2517.

Meier, A., Chang, J., Chan, E., Pollard, R., Sidhu, H., Kulkarni, S., Wen, T., Lindsay, R., Orellana, L., Mildvan, A., Bazner, S., Streeck, H., Alter, G., Lifson, J., Carrington, M., Bosch, R., Robbins, G., & Altfeld, M. (2009). Sex Differences in the Toll-Like Receptor—Mediated Response of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells to HIV-1. Nature Medicine, 15 (8), 955-959.

Meziane, H., Ougazzal, M., Aubert, L., Wietrzych, M., & Krezel, W. (2007). Estrus Cycle Effects on Behavior of C57BL/6J and BALB/cByJ Female Mice: Implications for Phenotyping Strategies. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 6 (2), 192-200.

Michael, S. (1976). Plasma Prolactin and Progesterone during the Estrus Cycle in the Mouse. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, 153 (2), 254-257.

Moore, C. (1992). The Role of Maternal Stimulation in the Development of Sexual Behavior and its Neural Basis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 662, 160-177.

National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement, and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3RS). (2008). Responsibility in the Use of Animals in Bioscience Research: Expectations of the Major Research Council and Charitable Funding Bodies. London: Tradewinds.

National Toxicology Program (NTP). (2006). Specifications for the Conduct of Studies to Evaluate the Toxic and Carcinogenic Potential of Chemical, Biological, and Physical Agents in Laboratory Animals for the NTP. Washington, D.C.: Government Publishing Office (GPO).

Palaszynski, K., Smith, D., Kamrava, S., Burgoyne, P., Arnold, A., & Voskuhl, R. (2005). A Yin-Yang Effect between Sex Chromosome Complement and Sex Hormones on the Immune Response. Endocrinology, 148 (6), 3280-3285.

Roof, R., Duvdevani, R., & Stein, D. (1993). Gender Influences Outcome of Brain Injury: Progesterone Plays a Protective Role. Brain Research, 607, 333-336.

Stoffel, E., Ulibarri, C., & Craft, R. (2003). Gonadal Steroid Hormone Modulation of Noiception, Morphine Antinoiception, and Reproductive Indices in Male and Female Rats. Pain, 103 (3), 285-302.

Tagliaferri, R., Compagnone, C., Korsic, M., Servadei, F., & Kraus, J. (2006). A Systematic Review of Brain Injury Epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochirurgica, 148, 255-268.

Taylor, K., Vallejo-Giraldo, C., Schaible, N., Zakeri, R., & Miller, V. (2011). Reporting of Sex as a Variable in Cardiovascular Studies using Cultured Cells. Biology of Sex Differences, 2 (11), 1-7.

Wagner, A., Willard, L., Kline, A., Wenger, M., Bolinger, B., Ren, D., Zafonte, R., & Dixon, C. (2004). Evaluation of Estrus Cycle Stage and Gender on Behavioral Outcome after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Research, 998 (1), 113-121.

Wagner, A., Sasser, H., Hammond, F., McConnell, F., Wiercisiewski, D., & Alexander, J. (2000). Intentional Traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Associations with Injury Severity and Mortality. Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 49 (3), 404-410.

Wald, C., & Wu, C. (2010). Of Mice and Women: The Bias in Animal Models. Science, 327 (5973), 1571-1572.

Wizemann, T., & Pardue, M. (2001). Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). Sex, Gender, and Influenza. Geneva: WHO Press.

Wright, D., Kellermann, A., Hertzberg, V., Clark, P., Frankel, M., Goldstein, F., Salomone, J., Dent, L., Harris, O., Ander, D., Lowery, D., Patel, M., Denson, D., Gordon, A., Wald, M., Gupta, S., Hoffman, S., & Stein, D. (2007). ProTECT: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Progesterone for Acute Traumatic Brain Injury. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 49 (4), 391-402.

Wu, J., Zelinski, M., Ingram, D., & Ottinger, M. (2005). Ovarian Aging and Menopause: Current Theories, Hypotheses, and Research Models. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 230 (11), 818-829.

Xiao, G., Wei, J., Yan, W., Wang, W., & Lu, Z. (2008). Improved Outcomes from the Administration of Progesterone for Patients with Acute Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Critical Care, 12 (2), 1-10.

Zucker, I., & Beery, A. (2010). Males Still Dominate Animal Studies. Nature

Editorials, 465, 690.

1997至2000年間,由於危及使用者性命,10種在美國上市的藥物被迫回收。其中八種被認為是「相較於男性,對女性的危險性較大」。雖然斥資百萬進行這些藥物的研發,卻也引起使用者死亡或造成痛苦。因此,這類研究不容一絲錯誤。

這些藥物失敗(而且女性使用者的失敗率更高)的一個原因是因為許多研究(不論人類、動物、細胞或組織研究)仍只使用雄性動物或檢體(見下圖)。

在排除生理性別差異前,雄性與雌性動物模式皆需安排於研究設計中。雖然這會增加基礎研究的花費,如果考量到研發生物醫學療法的昂貴花費,這樣的研究設計可能反而降低整體費用。可以確定的是這會降低受苦與死亡的人數。

國家一般都通過立法,要求政府資助的第三期臨床試驗必須包含女性受測者。然而,這些指導方針仍很少應用於動物、細胞或組織研究。這代表藥物和治療法可能對女性的療效較小,而且任何女性特有的反應都無法在研究開發時期觀測到。

性別化創新:

同時從兩種生理性別動物以及各種荷爾蒙狀態中取樣產出了可以影響藥物發展和病患照護的新發現。

-

研究動物模式的生理性別差異已經促使新的創傷性腦損傷(TBI,常見於男性多於女性)治療法問世。

-

以動物模式說明懷孕、動情週期以及更年期狀態可以顯示荷爾蒙對基礎分子路徑的生物影響,也對某些自體免疫疾病的瞭解至關重要。

-

調控因素已為了改善動物模式的毒性反應而考量生理性別差異;並且導致更有力的環境衛生標準。