探索為高齡者設計的輔助科技市場

議題

到了2050年,世界人口將劇烈地老化,對於急症照護和家庭健康服務的需求也會增加,從而使人力照顧資源、保險公司和社會系統面臨更多張力。因此,未來會需要更多新科技來幫助老年人獨立生活。

方法:工程檢核單

透過生理性別和社會性別分析來研究有關老年照護的數據資料,可發現輔助科技和機器人的新契機。研究者已針對兩性老化的不同需求進行研究,透過與年長者、其照護者和更多相關人等的合作,將可以提供工程師重要的設計和發展輔助產品的靈感,使產品能適用於更廣泛的使用者。

性別化創新:

- 評估女性和男性對於輔助科技的需求

- 發展出考量女性和男性需求的輔助科技

- 使用參與式設計,以創造出新世代的輔助科技

議題

性別化創新 1:評估女性和男性對輔助科技的需求

方法:分析生理性別和社會性別的交互作用

性別化創新 2:發展考量女性與男性需求的輔助科技

方法:參與式研究和設計

性別化創新 3:使用參與式研究和設計以創造輔助科技的下一世代

結論

議題

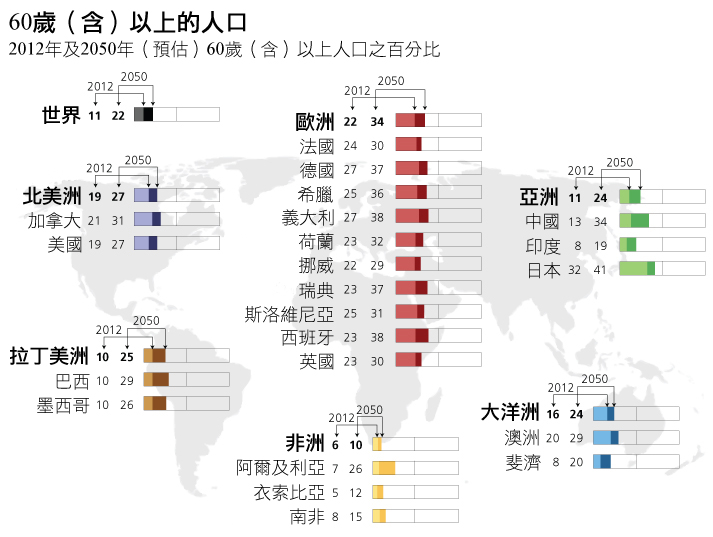

全球超過60歲的人口數將會持續增長,預計從當前的11%成長到2050年的22%,詳如下圖(資料來源:United Nations, 2012)。人口金字塔呈現老年族群逐漸增加,年輕族群則持續下滑,尤其是歐洲、美國及加拿大等地。隨著人口老化,將會有更多人需要照護(care)。在此同時,能提供當前西方社會以病患為中心的照護服務(patient-centered care)的人愈少,付得起的人也愈少。隨著更少人能提供照護,我們便需要新的解決之道,以因應提供照護者的減少。近年來,研究者致力發展科技來協助高齡照護(Peterson et al., 2012; Broekens et al., 2009)。

性別化創新 1:評估女性和男性對輔助科技的需求

瞭解高齡族群特性是設計成功輔助科技的關鍵。雖說年老女性和男性常有相似的需求,但認知生理和社會性別如何交互作用而影響老化,將可協助工程師發展出最符合老人需求的科技。一些研究顯示,生理與社會性別交互作用會大大影響高齡時期的健康。

- 失智症(dementia) 在老化過程中影響同等數量的女性與男性,但因為女性在已開發國家中較男性長壽,所以女性也更容易受失智症所困擾(Plassman et al., 2007; Nowrangi et al., 2011)。

- 關節炎(arthritis) 對同齡的兩性而言,在女性中更為常見。而類風濕性關節炎的發生率,女性更比同齡男性多出2-3倍(Alamanos et al., 2005; Linos et al., 1980)。

- 手指靈活度損傷(dexterity impairment) 在同齡兩性間對男性造成的衝擊較大(Desrosiers et al., 1995)。

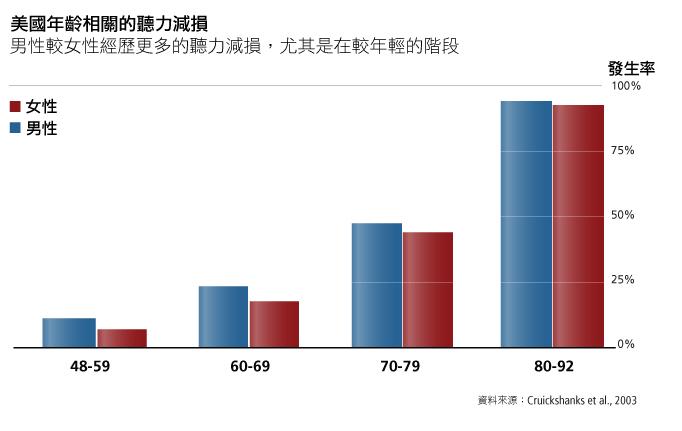

- 聽力損傷(hearing impairment) 在同齡兩性間較常發生於男性(Cruickshanks et al., 2010),詳見圖表。原因可能來自於特定生理性別的生物性的結果,也意味著男性較女性有更多的機會暴露在有噪音的職場中(Engdahl et al., 2012)。

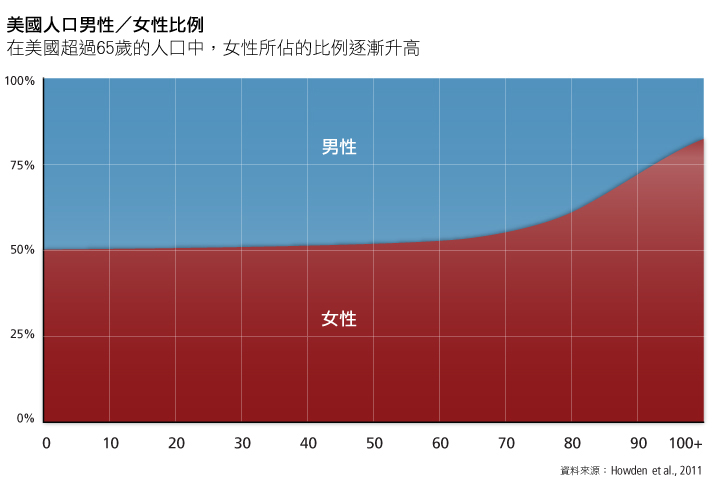

分析生理和社會性別對研發輔助科技工程的成功與否是很重要的,在人口持續老化的現代更是如此。美國的數據顯示,高齡者中多數為女性,且愈是高齡,女性所佔的比例愈高。在美國人口中,65-69歲者約有53%是女性;在「最高齡」的階段,也就是85歲以上的族群中,女性則佔65-80%,詳見下表。我們需要更關注這些數據:如果輔助科技研究不理會生理和社會性別,將大大地限制所研發之科技的市場性、有用性和可接受性。

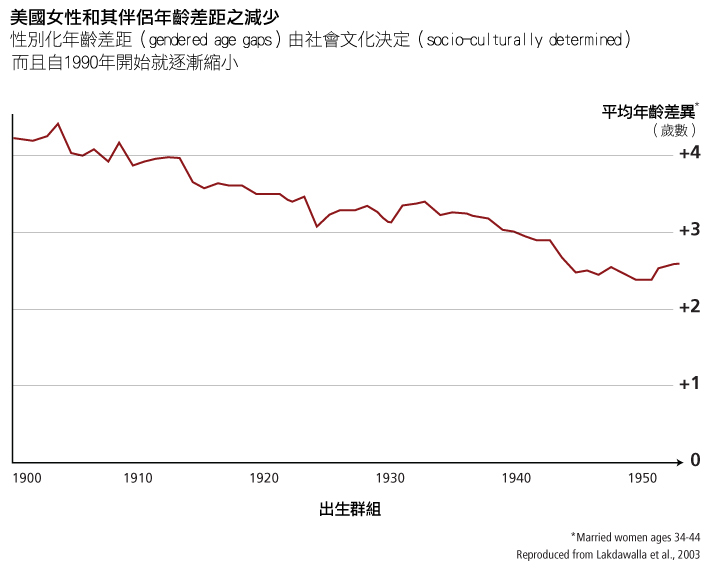

數據也顯示了伴侶模式中重要的社會性別差異,例如結婚年齡和伴侶關係裡的年齡差異。在西方社會中,女性傾向和比自己年齡稍長的男性結婚。在英格蘭和威爾斯,有數據顯示,女性平均與比自己年長2.6歲的男性結婚,最常見的年齡差距則是1歲 (Bhrolcháin, 2005)。 在歐盟國家和美國也可發現相似的價值觀 (Lakdawalla, 2003; Van Poppel et al., 2001)。 婚姻年齡差距(性別化的現象)加上女性較男性長壽,意味著女性較男性更有機會獨居。在美國,女性佔65歲以上人口的59%,卻佔了獨居人口的76%(Pew et al., 2004)。女性比男性更有機會因喪偶而單身,而大部分接著喪偶的就是孤獨(Dragset et al., 2011)。這可能就意味著,女性對能提供社交連結的輔助科技有較大的需求。

類似的模式也適用於同性婚姻和伴侶關係:在同性婚姻和登記伴侶關係得到承認(並且有數據)的瑞典,同性戀伴侶之間的平均年齡差距大於異性戀之間的伴侶。例如,有34%的男同性戀、15%的女同性戀和9%的異性戀在伴侶關係/婚姻中,年齡相差10歲(含)以上(Andersson et al., 2006)。有挪威人口統計學研究發現,男同性戀和女同性戀登記伴侶關係的平均年齡差異為7歲,而異性戀伴侶間平均年齡差異則是2.5歲(Kristiansen, 2005; Noack et al., 2005)。

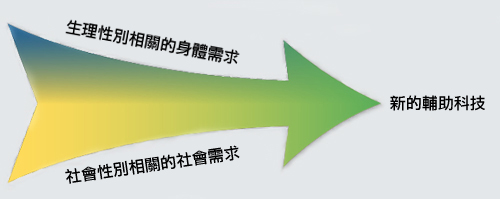

方法:分析生理性別和社會性別的交互作用

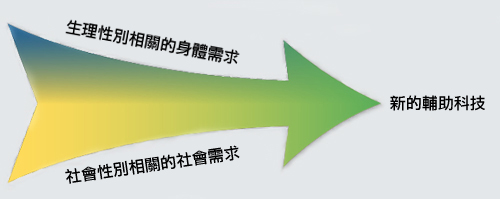

分析年長者的生理性別(身體需求)和社會性別(社會需求), 並分析這些身體和社會文化需求如何在個別女性和男性身上結合,可協助研究者設計出最有效而且具有市場的輔助科技。整體而言,設計者應注意女性佔高齡者多數的事實。分析生理性別差異顯示,女性和男性通常對身體活動能力、感知靈敏度的需求很不一樣。要有效設計的話,就必須把結婚年齡、伴侶模式、家庭管理經驗及對科技接納能力的社會性別差異,列入重要的考量。若欲探究輔助科技的市場,研究者就要考量女性與男性的高齡者或其照顧者的特別需求。

性別化創新 2:發展考量女性與男性需求的輔助科技

本章節將呈現如上所述回應女、男性需求所設計之輔助科技範例,並特別關注設計中的性別化創新。

- 視覺輔具(visual assistance):

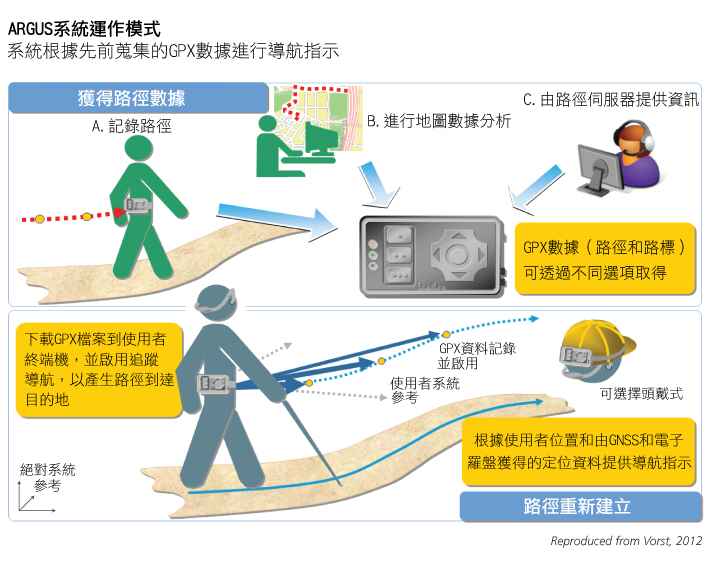

歐盟科研計畫FP7(European Union’s Framework Programme 7 (FP7) Project)-視障人士個人輔助導引系統( Assisting Personal Guidance System for People with Visual Impairment; ARGUS),打造為視力損傷人們的安全與自主行動系統 (Dubielzig et al., 2012)。 ARGUS設計成手持裝置,包括全球定位系統(GPS)、接收器和無線數據機,可確認使用者的位置並提供聲音和觸覺的導引,讓使用者在建築物和自然環境中可隨著預定的路徑行動 (Otaegui et al., 2012—見圖表)。

- 行動輔助設備(mobility assistance):

輪椅是重要的行動輔助,電動輪椅則可輔助那些力量不夠與(或)靈巧度不足以控制手動輪椅的人獲得行動力。然而,還是有些人無法操作電動輪椅 (Fehr et al., 2000)。 有鑑於此,研究者正研發機器人輪椅(robotic wheelchair)「Wheeley」,設計成可執行半自動導航。使用者不必動手控制輪椅的精細動作,而是可以透過發出一般性的聲音命令(例如「左轉」、「前進」等)來操控輪椅,隨後電腦的視覺系統將會決定採取何種路徑 (Bailey et al., 2007)。- 認知功能輔助設備(cognitive assistance): 智力訓練或可延緩認知功能衰退 (Wilson et al., 2010),已有許多發展中的科技可用來保持心智敏銳度,包括:

除了減緩失智症發生的計畫之外,歐盟科研架構計畫FP6「幫助罹患失智症者操控其生活」(COGKNOW),已發展出原型技術以協助失智症患者的日常活動。COGKNOW可以提醒使用者醫療預約和用餐時間、幫助使用者找出物件如鑰匙等,並支持使用者、照護者和醫療保健專業人員之間的聯繫(Bresciani et al., 2008)。

BrightArm復健系統:由美國國家衛生研究院(NIH)支持研發,可監控及訓練中風相關失智症患者手臂和手的動作(Rabin et al., 2012; Rabin et al., 2011)。該單位也支持研發中風患者用的機器人外骨骼,也希望能用於診斷和復健,且將會納入腦機介面(brain-machine interface)(NIH, 2012)。

一款使用者在模擬公寓中尋找物品的3D遊戲,由TechnischeUniversität Chemnitz進行研發 (Lange et al., 2010; Sitzer et al., 2006)。

一款記憶訓練遊戲,要求使用者記住購物清單並在虛擬便利商店中選購正確的商品,在香港進行研發測試 (Man et al., 2011)。

歐盟執行「用以監控並提升高齡者生活品質,具高治療值的資訊系統科技(IST)遊戲」之研發(ELDERGAMES)計畫,使用虛擬實境和專用硬體設施來訓練一系列技能,例如記憶力、推理能力和選擇性注意力(Gamberini et al., 2009)。

方法: 參與式研究和設計

輔助科技的研究與設計也可以透過和醫療保健專業人員和照護者的參與而獲益。在歐盟國家,為罹病或高齡成人提供非正式照顧者中,女性約是男性的兩倍(Daly et al., 2003)。美國研究者也有類似的發現—女性大約提供了70%的非正式照顧(Lahaie et al., 2012; Kramer et al., 1995)。科技設計者可以透過參與式設計納入這些照顧者多年的實務經驗(Landau et al., 2010)。例如,COGKNOW設計者透過諮詢女、男照顧提供者及與失智症患者有不同關係的對象(兒子、女兒、配偶、堂親等),以深入瞭解並運用此類知識(Andersson et al., 2007)。在芬蘭,研究者也探討受照護者和供照護者針對4個試驗性智慧家庭中60項輔助科技的回應(Melkas, 2012)—亦見:工程創新程序。

性別化創新 3:使用參與式研究和設計以創造輔助科技的下一世代

研究顯示,由預期使用者參與其中的輔助科技研發,其成果將有較高的接受率。在研發初期階段即納入未來的使用者能確保研發出的科技符合其需求(Ghorbel et al. 2008; Kanis, 2011)。McCreadie等發現,當輔助科技既聰明、簡單、可靠又能符合使用者的特定需求,就很可能融入日常生活(McCreadie et al., 2005)。

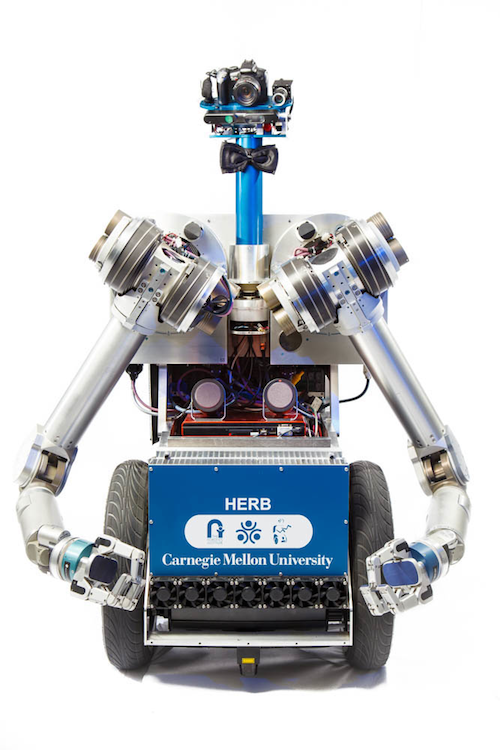

許多輔助科技將以手持、房間安裝設備等形式存在,僅在不顯眼處運作。然而有另一些輔助科技可能是機器人,須與智慧家庭環境合作運行,以解決如孤立和沮喪的社會心理狀態。機器人可能直接與使用者互動以監控其心理狀態、提供認知刺激、陪伴,以及提供複雜環境中的導航(Pollack, 2005)。Tapus等定義一些輔助科技使用於身體互動的條件,將可提升使用者的接受度,這些條件包括身體化、個性、同理心、承諾、接納與轉移(Tapus et al., 2007)。與人類產生互動的機器提供了更多的設計挑戰:

- 情緒:當工程師認知到情緒並非只是智慧的副產品,而是認知、專注力和學習力背後的驅動力時,人工智慧(AI)的定義正在改變(Minsky, 2007; Arbib et al., 2004)。在研發機器人的情感智力的過程中,表達的性別化差異可能將變得更重要(Brody et al., 2008)。「友善機器人(The CompanionAble robot)」透過在螢幕上數位呈現的「眼睛」來表達情感(CompanionAble, 2010)。

- 族群和膚色: 既有的臉部辨識演算法—用以辨識特定個人、偵測情緒信號等—通常對某一膚色對象有較好的表現。例如,在一場國際的競賽中,由東亞國家研究者研發的臉部辨識演算法,解讀亞洲臉部的精確度勝過對高加索人的精確度;而由西方國家研發出的演算法,對高加索臉孔的解讀準確度比亞洲臉孔還來得高(Phillips et al., 2011)。考量這些變項,對於發展機器人臉部辨識系統的全球市場是很重要的。

- 對個人空間的文化決定性感受: 對於個人空間的感知具有跨文化差異之說法是有案可稽的。在一文化中被視為「冷漠」的距離,在另一文化中可能被認為「咄咄逼人」(Fries, 2005)。對個人空間跨文化標準的研究,可能有助於輔助機器人以社會可接受的方式與使用者互動。

結論

女性與男性對於科技的需求和經驗具有差異。女性與科技接觸的經驗可能較少,也對科技抱持較不積極的態度(Gaul et al., 2010)。女性可能也對在家庭環境中使用如機器人等輔助科技有較多憂慮(Cortellessa et al., 2008)。因此,在科技設計中納入女性與男性是重要的。分析生理性別和社會性別並將女、男性使用者均納入科技研發過程,將有助於更好的設計,並提升產品的市場性。

研究者目前正研發新輔助科技,以協助高齡者獨立生活,並減輕照護提供者的負擔。透過和高齡者及其照顧提供者為伍的參與式研究和設計,設計者將獲得研發輔助產品關鍵的洞見,這對擴增用戶群相當有幫助。將使用者和相關人等納入設計過程中,將有益於成果。根據人口統計學數據進行生理性別和社會性別分析以打造機器,對於下個世代的輔助科技發展相當重要。

參考資料

Academy of Medical Sciences (2012). Human Enhancement and the Future of Work. Report from a joint workshop hosted by the Academy Medical Sciences, the British Academy, the Royal Academy of Engineering and the Royal Society.

Alamanos, Y., & Drosos, A. (2005). Epidemiology of Adult Rheumatoid Arthritis. Autoimmunity Reviews, 4 (3), 130-136.

Andersson, G., Noack, T., Seierstad, A., & Weedok-Fekjær, H. (2006). The Demographics of Same-Sex Marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43 (1), 79-98.

Andersson, S., & Meiland, F. (2007). COGKNOW Field Test #1 Report. Brussels: European Commission.

Arbib, M., & Fellous, J. (2004). Emotions: From Brain to Robot. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8 (12), 554-561.

Bailey, M., Chanler, A., Maxwell, B., Micire, M., Tsui, K., & Yanco, H. (2007). Development of Vision-Based Navigation for a Robotic Wheelchair. Proceedings of the 10th Annual Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, June 12th-15th, Noordwijk, The Netherlands.

Bengtsson, J., Castellot, R., Nugent, C., Dröes, R-M., Moelaert, F., Mulvenna, M., Meiland, F., & Haaker, T. (2009). COGKNOW: Final Report. Brussels: European Commission.

Bhrolcháin, N. (2005). The Age Difference at Marriage in England and Wales: A Century of Patterns and Trends. Population Trends, 120, 7-14.

Bresciani, M., & Lhoutellier, V. (2008). COGKNOW: Prototype Release of Multi-Modal Interfaces. Brussels: European Commission.

Brody, L., & Hall, J. (2008). Gender and Emotion in Context. In Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J., & Barrett, L. (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions, Third Edition, pp. 395-408. New York: Guilford Press.

Broekens, J., Heerink, M., & Rosendal., H. (2009). Assistive Social Robots in Elderly Care: A Review. Gerontechnology: International Journal on the Fundamental Aspects of Technology to Serve the Ageing Society, 8 (2), 94-103.

CompanionAble. (2010). CompanionLetter—Number 2.

CompanionAble. (2009). CompanionLetter—Number 1.

Cortellessa, G.,Scopelliti, M., Tiberio, L., Koch Svedberg, G., Loutfi, A., & Pecora, F. (2008). A Cross-Cultural Evaluation of Domestic Assistive Robots. Proceedings of AAAI Fall Symposium on AI in Eldercare: New Solutions to Old Problems. AAAI.

Cruickshanks, K., Zhan, W., & Zhong, W. (2010). Epidemiology of Age-Related Hearing Impairment. In Gordon-Salant, T., Frisina, R., Popper, A., & Fay, R. (Eds.), The Aging Auditory System, pp. 259-274. New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Cruickshanks, K., Tweed, T., Wiley, T., Klein, B., Klein, R., Chappell, R., Nondahl, D., & Dalton, D. (2003). The 5-Year Incidence and Progression of Hearing Loss: The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 129 (10), 1041-1046.

Daly, M., & Rake, K. (2003). Gender and the Welfare State: Care, Work, and Welfare in Europe and the USA. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Desrosiers, J., Hébert, R., Bravo, G., & Dutil, É. (1995). Upper Extremity Performance Test for the Elderly (TEMPA): Normative Data and Correlates with Sensorimotor Parameters. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 76 (12), 1125-1129.

Dragset, J., Kirkevold, M., & Espehaug, B. (2011). Loneliness and Social Support among Nursing Home Residents Without Cognitive Impairment: A Questionnaire Survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48 (5), 611-619.

Dubielzig, M., Classen, G., Lindemann, M., Görlich, J., Wegge, K., Patti, D., Marcoci, A., Otaegui, O., Loyo, E., & Foesleitner, C. (2012). ARGUS (Assisting Personal Guidance System for People with Visual Impairment): State of the Art of the Relevant Technologies and Standards. Brussels: European Commission.

Engdahl, B., Krog, N., Kvestad, E., Hoffman, H., & Tambs, K. (2012). Occupation and the Risk of Bothersome Tinnitus: Results from a Prospective Cohort Study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, HUNT). British Medical Journal, 2 (1), e000512.

England, P., & McClintock, E. (2009). The Gendered Double Standard of Aging in U.S. Marriage Markets. Population and Development Review—Data and perspectives, 35 (4), 797-816.

Fehr, L., Langbein, W., & Skaar, S. (2000). Adequacy of Power Wheelchair Control Interfaces for Persons with Severe Disabilities: A Clinical Survey. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 37 (3), 353-360.

Fries, S. (2005). Cultural, Multicultural, Cross-Cultural, Intercultural: A Moderator’s Proposal. Paris: International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language (IATEFL) Publications.

Gamberini, L., Martino, F., Seraglia, B., Spagnolli, A., Fabregat, M., Ibanez, F., Alcaniz, M., & Andrés, J. (2009). Eldergames Project: An Innovative Mixed-Reality Table-Top Solution to Preserve Cognitive Functions in Elderly People. Proceedings of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Second International Conference on Human Systems Interactions, May 21st—23rd, Canatia, Italy.

Gaul, S., Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M. (2010). Accounting for User Diversity in the Acceptance of Medical Assistive Technologies. Proceedings of the 3rd International ICST Conference on Electronic Healthcare for the 21st Century, eHealth.

Ghorbel, M., Arab, F., and Mokhtari, M. (2008). Assistive Housing: Case Study in a Residence for Elderly People. In Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, pp. 140–143.

Howden, L., & Meyer, J. (2011). 2010 Census Briefs—Age and Sex Composition. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

Kanis, M., Alizadeh, S., Groen, J., Khalili, M., Robben, S., Bakkes, S. & Kröse, B. (2011). Ambient Monitoring from an Elderly-Centred Design Perspective: What, Who, and How? Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Ambient Intelligence (AMI-11), Amsterdam.

Kramer, B., & Kipnis, S. (1995). Eldercare and Work-Role Conflict: Toward an Understanding of Gender Differences in Caregiver Burden. The Gerontologist, 35 (3), 340-348.

Kristiansen, J. (2005). Age Differences at Marriage: The Times, They Are A Changing? Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Lahaie, C., Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2012). An Uneven Burden: Social Disparities in Adult Caregiving Responsibilities, Working Conditions, and Caregiver Outcomes. Research on Aging, 1-32.

Lakdawalla, D., & Schoeni, R. (2003). Is Nursing Home Demand Affected by the Decline in Age Difference Between Spouses? Demographic Research, 8 (10), 279-304.

Landau, R., Auslander, G., Werner, S., Shoval, N., & Heinik, D. (2010). Families’ and Professional Caregivers’ Views of Using Advanced Technology to Track People with Dementia. Qualitative Health Research, 20 (3), 409-419.

Lange, B., Requejo, P., Flynn, S., Rizzo, A., Valero-Cuevas, F., Baker, L., & Winstein, C. (2010). The Potential of Virtual Reality and Gaming to Assist Successful Aging with Disability. In Jensen, M., Molton, I., & Kraft, G. (Eds.), Aging with a Physical Disability: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Linos, A., Worthington, J., O’Fallon, W., & Kurland, L. (1980). The Epidemiology of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota: A Study of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology, 111 (1), 87-98.

Man, D., Chung, J., & Lee, G. (2011). Evaluation of a Virtual-Reality-Based Memory Training Programme for Hong Kong Chinese Older Adults with Questionable Dementia: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27 (5), 513-520.

McCreadie C., & Tinker A. (2005). The Acceptability of Assistive Technology to Older People. Aging and Society, 25, 91-110.

Melkas, H. (2012). Innovative Assistive Technology in Finnish Public Elderly-Care Services: A Focus on Productivity. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment, and Rehabilitation, Online in advance of print.

Minsky, M. (2007). The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind. New York: Simon and Schuster.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2012). NIH Announces National Robotics Initiative Awardees. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services.

Noack, T., Seierstad, A., & Weedon-Fekjær, H. (2005). A Demographic Analysis of Registered Partnerships (Legal Same-Sex Unions): The Case of Norway. European Journal of Population, 21 (1), 89-109.

Nowrangi, M., Rao, V., & Lyketsos, C. (2011). Epidemiology, Assessment, and Treatment of Dementia. Journal of the Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 34 (2), 275-294.

Otaegui, O., Loyo, E., Carrasco, E., Fösleitner, C., Spiller, J., Patti, D., Olmedo, R., & Dubielzig, M. (2012). ARGUS: Assisting Personal Guidance System for People with Visual Impairment. Paper Presented at the 17th International Conference on Urban Planning, Regional Development, Information Society, and Urban / Transport / Environmental Technologies (REAL CORP)— Remixing the City: Towards Sustainability and Resilience?, May 14th-16th, Vienna.

Peterson, C., Prasad, N., & Prasad, R. (2012). The Future of Assistive Technologies for Dementia. Gerontechnology, 11 (2), 195-202.

Pew, R., & Van Hemel, S. (Eds.). (2004). Technology for Adaptive Aging. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Phillips, P., Jiang, F., Narvekar, A., Ayyad, J., & O’Toole, A. (2011). An Other-Race Effect for Face Recognition Algorithms. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Transactions on Applied Perception (TAP), 8 (2), 14-25.

Plassman, B., Langa, K., Fisher, G., Herringa, S., Weir, D., Ofstedal, M., Burke, J., Hurd, M., Potter, G., Wodgers, W., Steffens, D., Willis, R., & Wallace, R. (2007). Prevalence of Dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. Neuroepidemiology, 29 (1-2), 125-132.

Pollack, M. (2005). Intelligent Technology for an Aging Population: The Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Assist Elders with Cognitive Impairment. AI Magazine, 26 (2), 9-24.

Rabin, B., Burdea, G., Roll, D., Hundal, J., Damiani, F., & Pollack, S. (2012). Integrative Rehabilitation of Elderly Stroke Survivors: The Design and Evaluation of the BrightArmTM. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 7 (4), 323-335.

Rabin, B., Burdea, G., Hundal, J., Roll, D., & Damiani, F. (2011). Integrative Motor, Emotive, and Cognitive Therapy for Elderly Patients Chronic Post-Stroke: A Feasibility Study of the BrightArmTM Rehabilitation System. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) International Conference on Virtual Rehabilitation (ICVR), June 27th—29th, Zurich.

Sitzer, D., Twamley, E., & Jeste, D. (2006). Cognitive Training in Alzheimer's Disease: A Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 114 (2), 75-90.

Soler, A. (2012). ARGUS: Assisting Personal Guidance System for People with Visual Impairment. First Version of the Dissemination Plan. October 30.

Tapus, A., Mataric', M. J., & Scassellati, B. (2007). The Grand Challenges in Socially Assistive Robotics. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine, 14(1), 35-42.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Population Division. (2012). Population Ageing and Development—2012. New York: United Nations.

Van Poppel, F., Liefbroer, A., Vermunt, J., & Smeenk, W. (2001). Love, Necessity, and Opportunity: Changing Patterns of Marital Age Hegemony in the Netherlands, 1850-1993. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 55 (1), 1-13.

Vorst, D. (2012). ARGUS, Assisting Personal Guidance System for People with Visual Impairment. REAL CORP 2012.

Wilson, R., Barnes, L., Aggarwal, N., Boyle, P., Hebert, L., Mendes de Lyon, C., & Evans, D. (2010). Cognitive Activity and the Cognitive Morbidity of Alzheimer Disease. Journal of the American Academy of Neurology, 75, 990-996.

到了2050年,世界人口將劇烈地老化,對於日本、歐洲和美國來說尤為如此。大量的老年人口將會導致人力照顧資源和健康、社會系統的張力。本案例研究試圖在設計老年人的輔助科技時,納入對於生理性別和社會性別的考量。

輔助科技能協助年長者獨立生活,當研發這些科技時,注重生理性別差異是很重要的。例如,女性通常活得較久,但可能有較多會導致衰弱的疾病;例如,男性通常較早喪失聽力。此外,關注社會性別的差異也很重要:當女性和男性老化時,通常有不同的伴侶模式(例如年長女性較常獨自居住),男女也常有不同的家戶管理經驗,對於科技的接納能力也有所差異。我們鼓勵研究者分析生理性別和社會性別如何在個別女性/男性間交互作用,以使研究者能設計出更有效且具市場性的輔助科技—設計者當然希望自己的產品是有用的,且能對女性和男性都有吸引力。

當輔助科技變得越來越個人化,社會性別議題就顯得特別重要。美國、歐洲和日本的工程師正研發可以幫助高齡者的機器人。例如,Georgia Tech已創造出名喚Cody的機器人護理人員,可以為高齡者沐浴。由於沐浴是較親密的活動,故需要更謹慎地思考—為了女性和男性皆然。Carnegie Mellon正研發HERB(家庭探索機器人管家,Home Exploring Robot Butler),其可以為使用者協助取得家居用品、提醒使用者服藥,甚至打掃使用者的廚房。如果真有可以打掃廚房的機器人,我要立刻訂購它!

當這些機器人進入我們的生活,我們這些人類常會將它們性別化。關於合成語音的研究(機器發聲)顯示,人類聽眾會為機器聲音分派性別;意即,我們會轉譯、解讀這些機器聲音,把它們當成女性或男性的聲音,即便研究者的本意可能是創造出性別中立的聲音也是一樣(見:機器發聲)。蘋果的Siri(最初的iPhone聲音)是有趣的例子。當問Siri為何她是女性時,其中一個回答是:「我並未被指派性別」。此回答暗示著,為Siri指定性別不是蘋果的錯,而是聆聽者的。當使用者將一聲音解讀為陽剛的或陰柔的,將可能把所有文化刻板印象轉移到機器上。

性別化創新:

當設計新的輔助科技時,把生理性別和社會性別納入考量,將是確保產品獲得所有使用者歡迎的重要因素之一。

- 評估女性和男性對輔助科技的需求。

- 發展出考量女性和男性需求的輔助科技。

- 使用參與式設計,以創造出新世代的輔助科技。